Speaker 0 00:00:00 <inaudible>

Speaker 1 00:00:21 How are you doing? I'm Doug Giovanni and you're listening to the plastic podcasts, tales of the Irish diaspora. We all come from somewhere else.

Speaker 0 00:00:30 Three scientists from London proposed Ross, the Bob's potatoes, finally, into a tall wash, the poll strain, repeat each drive and Pope on a griddle mix with oats on the flour to make a bread. 70,000 leaflets were printed in English ROS with what the peasants carbons had no ovens, the black poach stunk light bread didn't catch on.

Speaker 1 00:01:10 Now we're a fairly prosaic bunch here at the plastic podcasts. Anyone who's read the

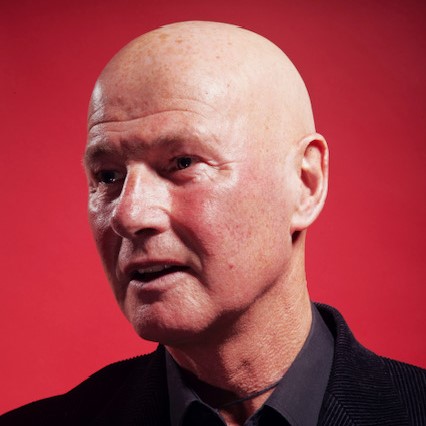

[email protected] will know there's not much lyricism at work here, but that all changes today with our guest poet cherry Smith born in Antrim. She had her first collection when the lights go up published in 2001, and has since had three further collections and a novel go to print her latest work. Famished is a heart rending Lee, beautiful account, the potato famine it's events and effects. And you just heard an extract there, to be honest, I'm fairly daunted by the prospect of talking to a bonafide poet. So I think I'll ask how you doing

Speaker 2 00:01:49 Good. Yeah, the sun is art. Um, and, uh, yeah, it's a glorious autumnal morning in North London.

Speaker 1 00:01:58 How do you normally spend your days apart from psych? Um, you know, being interviewed by various,

Speaker 2 00:02:03 Well, usually two and a half days a week. I work at the university of Greenwich on my teach poetry, which is often teaching people to trust their voice and to use their voice, which I love. Um, then the other two days I'm running around trying to make the rest of my living as a poet. And I also write about art, particularly painting. Do you think people don't trust their voices enough? Definitely not. Um, they've kind of got this voice that is grafted onto them and you can see it particularly with, you know, them were working class women, you know, young, black man. There's a fear of speaking from their true selves. And I say, you know, who are you in this? Why are you using white characters? Um, is this how you feel? What do you want to say about what's happening with Islamophobia or black matter? Um, it's kind of like, they, they think there's a voice that you must use for poetry. That's kind of 19th century. And then there's, uh, there's feelings that you must have in poetry that are some heart already received. You know, that's the whole question of, you know, trusting yourself to break art of the constriction of language or class or identity, but bring all of yourself with you. And then we get into talking about cliches, which is another whole way that we reduce language and reduce our voices and reduce or imaginations.

Speaker 3 00:03:36 Is this where you thought your life would be going when you were say 14? 15?

Speaker 2 00:03:40 Yeah. It's an interesting question. I don't really think about the future much. I was talking to a friend about that recently. He's also from the North and we were saying, did the troubles have that effect of not allowing us to believe in a future? We might be maimed. We might be dead, you know, that sort of living through, you know, terror really? Um, or is it more of a personality trait? I, I always felt like an outsider in my home and in some ways in, in the Tarn and the culture. So I thought the way to be an insider was to get away from there. But I think again, that's just a very deep personality trait. Um, I kind of didn't want to become a teacher, um, because it seemed that women taught and then they married. That was the kind of plan. Um, but I see lecturing in something I love, um, really teaches me a boat poetry itself on a boat, myself and my writing. So it feels very organic.

Speaker 3 00:04:52 So going then back to, um, being 14 years old in Northern Ireland, what was life like then for you?

Speaker 2 00:04:59 Well, I suppose I had experienced five years of the troubles and, um, can't remember when we had a huge bomb in my, the time I went to school in. Um, and if it had been 15 minutes later, there would have been a lot of school children killed or injured, um, was just before we got out of school and the main street there. Um, so it was a state of super vigilant being searched, going into shops, uh, making a broad detour around any, uh, you know, parked cars that were empty in the Tarn. Um, yeah, I think it, I think it just made me, um, on one hand this vigilance and then another hand, you know, I was a teenager, so I wanted to go out and start meeting guys and drinking and you know, saying, well, it's fair if something happens to me. So you have these, which is sort of interesting when I look at young people know around Corona virus, you know, I completely understand that I don't care if I get it. You know, they like the will to live and meet people and have fun is so powerful and not in the early stages of adulthood. Isn't it,

Speaker 4 00:06:21 But actually speaking of coronavirus as well, I mean, there's certainly, I'm aware that you ended up as a kind of site spider sense almost of everybody around you, you know, um, are they wearing a mask? I'll be like, am I too near I'll I'll I'll um, I'll, I'll die too near and things like that was that a kind of microcosmic version of what you are sensing in Northern Ontario.

Speaker 2 00:06:41 I think you kind of accrue it so gradually that you don't even realize you're doing it. And then when I had American friends who came back home with me in my twenties and they said, you know, what was it like? And I said, Oh, well, it was pretty normal. Except we did this, this and this. And, um, I realized how deeply it had effected me. And when I used to go for a walk, even when I came to England and I'd be walking somewhere, and if I saw a mile on the Ryzen or two men, I immediately thought, what are they doing? What are they digging up? What are they burying? There was a sense of, um, menace of, yeah. This kind of fear or this mysterious and menacing fear or, um, um, I suppose also driving along the road and coming behind an army truck and the guys sitting, training their rifles on you. And that's an incredibly unnerving experience, uh, where, uh, you know, if you pull in or you can't overtake you, you you're just sort of held in this horrifying magnetism. Um, um, while I didn't grow up in dairy or Belfast, there were all these other frames of, um, you know, militarism everywhere and powering paramilitary stuff. Uh, you driving home from somewhere and you get stopped by someone flashing a light and you don't know what they're doing, how official it is and that, that made you, um, yeah, very defensive and, uh, outraged at the same time.

Speaker 2 00:08:28 I don't think so. I really don't think so. I went to a play. I remember at the Riverside theater, I can't remember it was an Irish woman writer and there was a bomb blast in the, in the middle or near the end of the play. And I just burst into tears. I was so physically shocked and I couldn't stop crying. And of course it wasn't the play. It was, it was just the cumulative effect. And I thought, why didn't she warn this? But she didn't warn us because that would have ruined the dramatic moment. I think it, um, it's obviously transformed a lot by my writing, looking at the troubles and looking at colonialism and then the famine. And I think it does change how I hold it and how I see it, but just, I did a reading of my piece recently and because of the virus and the way the British government's handling it and mishandling it, I felt this rage about how they handled the pharma and how they were prepared to sacrifice millions of people. And it's a very similar rhetoric. So I think, yeah, I'm very interested in those genetic scars of, of trauma and how you process them,

Speaker 3 00:09:48 Something that you mentioned, which is the, uh, the bomb blast that took place, um, just by your school, what was the impact there on the, on, on the, on, on, on yourself and your school friends at the time?

Speaker 2 00:09:58 It was funny because there was a mixture of life as normal. Let's not talk about it. And then there would be these bomb scares during double maths. So girls got their boyfriends to ring up, say, there's a bomb, and then we'd all be disrupted. Um, you know, it, um, I remember the headmistress sang something. If there's another bomb scare, it will be double maths on a Friday afternoon for everyone. And the bomb scare stopped for a while. So, you know, it's, it's a weird thing to, you know, think it was a bit like a fire drill. Oh no, you'll go out and you stand in the cold and then you go in again and it was, it was there, but not there. That kind of which I suppose, in some ways we're living now, or we have to continue as though we're not going to get ill or we're not going to lose our loved ones because you can't operate in a state of constant fear. Although obviously many people have to in more situations, but there's still, um, yeah. The edge between what is normal and what isn't is. I got used to that. And funnily enough, when I, when I went to Israel, Palestine, I felt quite, I wouldn't say at home, but I felt a familiarity. It was not prepared for being searched, going into cafes, seeing people with weapons. I thought, Oh yeah, I know this world. And that was a shock. Um, yeah,

Speaker 3 00:11:40 You're listening to the plastic podcasts, tales of the Irish diaspora. We all come from somewhere else, find out more and subscribe to

[email protected]. Carrie Smith is a formidable with a truly original

Speaker 5 00:11:54 Voice. And I wanted to know when it was that she realized her love of poetry and when she made the decision to become a writer

Speaker 2 00:12:01 Very early on. Um, and I, I noticed this when I was in Ireland quite a lot under locked on and I would have dinner with friends. And then we would sit around and someone would say, give us a song, give us a poem. And there was no sense of it being a big performance or anyone taking up space or showing off. It was just hard. The evening was shipped. And if I was going to do that in England, I would have to say, you know, we might have poems and songs bring a poem or a song, but people just came with those things. And when I grew up, we had a very big extended family and they were quite religious, some of them, so they didn't have telly. And when you went right into their hosts, that we have these big sing songs and everybody had to do a turn.

Speaker 2 00:12:55 So you have to learn bits of Bible verse or a song or a poem. And these poems could go on for 20 verses. So it was very much seen as something that was, um, admired and important and part of the family culture. Um, um, I think, I don't know if that was unusual in a Protestant home, but it was, um, definitely part, part of how I gauged, well, certainly how I learned some things about performing and, um, enjoying it. And then I started to write poems probably very, very early, like seven or eight. Um, um, I just loved reading poetry poems read to me by my mom. And, you know, as soon as I started reading, I started to write art things that I love. So I was always collecting images and ways of describing things. I just find that extraordinary, the sort of comfort and beauty I find in language.

Speaker 2 00:14:02 So yeah. Being a poet, I, yeah, I don't know when that kind of got knocked out of me a bit when I went to Trinity, because there was a sense that you have to be a white, straight mom to be a poet. And, and also how could I write, like some of them like Auden or like McNeese or like Elliot, it was a sense that you could never do it really. And when I came to London, then there was a big, um, art burst of spoken word. Um, you know, I just went to these open mic nights and very, very informed by feminism and by the politics of the time, the peace CND marches, things like that. And the politics, the activism kind of restarted reignited. My love for poetry, um, gave me that context, that live context, which I think is so important for some poets to have an audience there that they can write to. And that, that encourages the voice and the expression, the courage.

Speaker 4 00:15:08 That's probably about the early eighties. Yes.

Speaker 2 00:15:10 Mid eighties, mid eighties, late eighties. Yeah.

Speaker 4 00:15:14 Yeah. Um, there seem to be sort of this immediate kind of almost punk post-punk explosion of sort like a, of spoken word and of, uh, uh, poetry magazines, and, um, uh, like you say, C and D suddenly there was a whole protection survive, protested survive thing. We came, we came kind of big and well, looking back on that, do you think there's any particular reason for that kind of turning points? Or do you think that was just, I don't know, just a perfect storm of events.

Speaker 2 00:15:41 Yeah. I wonder what encouraged it, there was a lot of, uh, input from the GLC to community groups and a lot of talk about political identities and encouraging people with different voices to speak art, a lot of funding for kind of community writing ventures. I mean, I was, I went to the Irish women's center, um, quite a lot on RO led the writing classes there. I also led writing in classes in a Jewish care, all peoples home, which was great fun. It was that sort of sense that, you know, you got paid and there was, there were places where that was nurtured and people like Benjamin's stuff, Elia, Linton, quizzy Johnson, those people were, you know, key to that explosion and yeah. Why did it happen then? It was, it was in response to police arrestment and, you know, I guess a right wing government. It, uh, um, you know, it's there in different forms and are, and it's, it's still vibrant. It's going through a whole new vibrancy, which is fantastic. And I, yeah, it's a, it's an interesting question though. Why did it happen then? Um, Hmm. I'm not really sure.

Speaker 4 00:17:11 Um, I'm kind of interested in the notion of turning points sometimes and whether or not there are such a thing as is such a thing as a turning point or whether or not it's just simply the oldest son you look back and go, Oh, that changed. Yeah.

Speaker 2 00:17:21 And why was George, George Floyd at a turning point where perhaps Philandro Castile, you know, was a turning point in a different way, but I mean, that was just a shocking, just as horrific. Um, and it wasn't to do with the lockdown and the pressure and the, the F the feeling, you know, of, I can't, I can't sit around anymore and take this, and it was a need to get known in the streets and the need to fight for something that you could fight for. Um, whereas with coronavirus, who are we finding, you know, it's a very amorphous difficult thing, and we're all vulnerable in a totally different way.

Speaker 4 00:18:02 And do you think poetry is part of that in the finding of your own voice?

Speaker 2 00:18:06 Absolutely. Yeah, I do. I, um, I I've seen it with, you know, young students who don't know what they're writing a Bart and, uh, and are kind of not, not really engaged. And then you see, you know, higher about writing, about what happened last week with killer malls and them day. Tell me about that. How did that feel? Cause I can't tell you about it. And then, you know, one of my students started to write about what it felt like to not go out that day. Cause she was, she was frightened of getting her head, chop pulled off her head and she wrote a really angry, fantastic poem. Um, you know, that was the beginning of her feeling like she had permission.

Speaker 4 00:18:52 And when did you feel that you have permission to become a poet again then?

Speaker 2 00:18:56 Well, definitely around, I think it was called, there was something like the wild women cafe, which was funded by the GLC in the center of town. And I used to go to that and it was, you know, a combination of the SIF, probably women only space that enabled me to speak and get rid of this kind of weight of the patriarchal, common, which of course, much of it, you know, I'm part of that as well. I'm, you know, imbued in it like McNeese and yet, but it was great to say, okay, I don't need them and I can, I can, uh, thrive in my own way, I suppose.

Speaker 4 00:19:35 So you'll first, um, collection of poems came out in 2001. Yes. Um, and just going back to that, how did that feel?

Speaker 2 00:19:42 Well, I really felt that took a long time to get published and it was, I was ecstatic. I think when you have your first book published, there's nothing like it. And to have a launch in Belfast and have my whole family and friends come to it and people, I didn't know, it was yeah, very, very important. Um, uh, very empowering and yeah, moving I suppose as well.

Speaker 4 00:20:14 And we then move on to, um, writing a novel. It was not a very, very different experience for you.

Speaker 2 00:20:21 Yeah. Um, I read recently a definition. What's the definition of, you know, the difference between poetry and prose and the differences, pros, everything we're talking in this pro the minute you try to define it, but I like the definition of poetry is like splashing into a pool. Um, a novel is doing lengths. Um, it's, it's a long form there's, there's sustained, you know, very careful, you know, long view. Um, I'm more of a short view person. Really. I like, I like the splash. I like working on a poem for a few weeks and then it can almost be published. I mean, that's, that's wonderful. Um, probably very impetuous that way, but it was very, very good training to write a longer piece and to be really involved in that world. Um, wake up every morning and do that sort of lucid dreaming, what are my characters going to do today and where are they going to go?

Speaker 2 00:21:21 And then feeling that loss when they're gone, that was, that was just really empowering and wonderful. And, um, I did feel a little bit of a betrayal of poetry and poets, which was, I didn't expect because you know, it was writing, working on the novel for a few years. I didn't write much poor G it kept a little bit going, but it was very cinematic. And, you know, to have, rather than just a shot in your head, you have a cinema, the whole film in your head, um, that was really accompanying in a different way to poetry. And I suppose I write poetry to discover an insight and emotional or intellectual insight. And in the novel, I ended up, uh, stowing those insights to characters and that felt very different. It felt generative in a different way. And it felt like I was talking to the bigger world, um, which sometimes with poems, you feel you're talking to your lover or your mother and nobody else would get it. And it is quite amazing that they do. But

Speaker 3 00:22:33 So there's a kind of shared intimacy with poetry.

Speaker 2 00:22:35 Yes. Yes.

Speaker 3 00:22:38 And so when people come up to you with responses to that, and either you feel, Oh yes, absolutely. You got it or no, that's not what I meant at all, but you've taken this from it. I mean, what's, what's what, what's your, what's your take on that?

Speaker 2 00:22:53 I'm sometimes surprised when I write something that is very personal and particular and people are moved by it and it hasn't, it wasn't their experience, but they're obviously touched by the emotional charge of it. Um, when they bring something I didn't see in it, generally I find that really invigorating. And I love the surprise of that because the poem is off on its own little feet going into someone else's hearts and meaning something else that, yeah, I didn't plan it's, it's, it's wonderful.

Speaker 3 00:23:34 Which brings us neatly or raggedly, uh, across the famished. How long did it take you to, to, to, to write the, um, the, the, the, the cycle of poems?

Speaker 2 00:23:46 Probably it was over two years. I think the reading that going to family and villages, museums, the walking around condom, Mara or bearer, um, yeah, uh, probably two years. Yeah.

Speaker 4 00:24:04 Uh, as, uh, as I understand this, um, th there's all began with it with a, with a chance encounter with a poster in the London underground.

Speaker 2 00:24:11 Yeah. It was a painting by an artist called Thomas Sully. And it was a painting of queen Victoria as a young woman, beautiful painting. And it was advertising an exhibition about her life on her role as queen and mother and, um, um, someone had written or scratched rather, uh, across the surface of, of her forehead, Irish farmer. And I remember just feeling that like a slap and I looked around the stuff, I could see the person who done it and I wanted to hug them. And I suddenly realized that I had a raised it. I had a faced it. I had, you know, I just didn't know what queen Victoria did during the farmer. And I wanted to know, and I felt, I should know, um, that little bit of graffiti was in 2012 and it was just churning over in my head. And I, I, I thought I must do something.

Speaker 2 00:25:11 And then I thought, no, no, no, it's too hard. And it's too emotional. And I can't, I'm not up to it. And then it came back probably in 2016, you've got to do it. And that was inspired by the migrant boats coming across the Mediterranean and just, you know, feeling the despair and awful, you know, tragedy of their lives. And then feeling, I didn't know enough about the coffin ships. I knew there were these things called coffin ships, but I wanted to know what those crossings were, where like, who, how many people took them, where did they arrive? How was life when they arrived? So I, I just felt that impetus to inhabit it and inhabit my own history and work hard. What was myth and what was fact and how I could move between those things with a poem

Speaker 4 00:26:03 Move between them. Lots of things, actually with the, with the side components, don't you, I mean, there's, um, there's historical research, there's, um, extracts of speech and newspaper article, uh, from the time there's also a bit, so children's nursery rhyme and so on is not just simply a lyrical response, but a, but a whole amalgam of different influences in that. Um, was, was that just something that the, the, the fed into it, as you, as you were doing the research or was this part of something that was pre-planned there?

Speaker 2 00:26:35 No, none of it was pre-planned. I just kept having these voices. One of the first voice came before I'd done any, um, I was sitting anonymous, Kerig the Tarun Guthrie center, and I thought my, I did live in New York in the late nineties, and I thought, wow, what would it be like to be a woman who grew up in Arland, in rural Ireland with so little, um, speaking Irish and leaving, losing her husband and children on the way. And so you arrive, you're living in the Bari in New York and slum, and you might have a symbol. That's all you have. Um, those things just began that poem, you know, what do you call a woman with no husband, a widow watch color, a woman with no children, a mother with no children, the poor. So, and I thought hard to she, how does she inhabit that grief?

Speaker 2 00:27:36 And that idea, I heard that some, um, migrants to America never wanted to go near the sea again. And some people never wanted to date a potato again. And when you, you know, you realize that sort of a version that becomes part of your life, that, that just that voice came out. And then I kind of more consciously looked for women's voices that I couldn't inhabit in that way. Um, such as the young woman who ended up in Australia as a, uh, Earl gray orphan, they, they took 3000 girl or firms from the work houses in Ireland, North and Cyrus, and sent them out to Australia, basically to be wives for Australian man. And one was so distressed when she got there. They, they wanted to put her in a psychiatric care and the doctor said, you know, she, she just needs love, she's been traumatized.

Speaker 2 00:28:35 Um, and so that idea of this girl who'd lost everything, what was her voice like? And that was a very haunting place to be because it was so unhinged. And I, I felt like it was such an unhinging experience for so many people, those dying, those who survived. Um, so there was that kind of 10 are going through it. And then when I find the quotes by the Earl of Clara and then, or by Trevelyan, they were so stark. And so, you know, unremittingly racist and I didn't want some habit, those man, um, I didn't want it to be seen as being, um, massaged by art. I wanted it just to be very stark, um, with things like the nursery rhymes. I, I don't know who wrote one of the tier two, but tier two, it was an anonymous, um, rhyme, but I grew up with it.

Speaker 2 00:29:36 And, um, then I, I wanted to also echo that with some of the rhymes I wrote. So there was sort of lyrical voices, historical passages, and then responses to, um, Eritrean poets who were writing about Africa famine. And the idea that, how do I respond to starfish to lie as a person living with white privilege in the West? How do I see a starving person? And I felt like it wasn't just a challenge to historical imperialism. It was also challenged to how we respond today to the ongoing issue of farm on the ongoing use of political use of hunger and dehumanization of, of, um, the people through the experience of family.

Speaker 1 00:30:32 <inaudible>, we'll be back with Jerry Smith in a moment, but first the plastic pedestal, where I asked one of my interviewees to nominate a member of the diaspora of personal or cultural significance to them this week, Tony Murray steaks a claim, a nice sense revolution in the air of the politesse kind of,

Speaker 2 00:30:55 You actually stole my thunder a bit because I was going to have died down. Um, Oh, I think you might've already done it. Um, but, uh, um, if I may, I would like to have Dave Allen because he, for me was so much a part of my kind of childhood adolescence growing up, my sense of, well living here in London, I've been connected to Irish humor and Irish life. And, um, I, um, I remember seeing him in one of his very, very early appearances who's about Dooney can show nearly sixties. My mum and dad used to watch it avidly, you know, the kids used to kind of, I suppose, you know, put up with it kind of thing. Um, we'd sit there and sit through it. And then this guy comes on, Val dune can introduced a new comment and he comes on and he's absolutely brilliant.

Speaker 2 00:31:57 Um, uh, so you got his own show quite soon. And we watched, we watched, um, one of the things I loved about Dave Allen was his stories. Do I, he told ghost stories often too. We used to lower the lines in the studio. Uh, so these, these ghost stories, as well as the jokes, um, that reminded me of my uncle Michael in Ireland, you know, he used to tell us those stories. We were kids when on holidays. Um, but Dave Allen was just so cool. He was like, you know, there's 60 students. Um, and they know, I, I kind of went off in the pit, I think in the eighties, I didn't really follow his career much. He seems to sort of, I felt, I dunno, they hate ping pong, the old guard. And then we got this new alternative comedy Cohen, um, which came along and, um, then someone else me, uh, was someone offered me a ticket to go and see him in London on stage, like real, you know, he's not on salary.

Speaker 2 00:33:10 I said, no, he does stand up again. He's coming back to doing the boards. And it was frankly, I wasn't particularly enthusiastic about going because I just thought, nah, it's not really the eighties. It's not kind of a thing. This is late eighties. Uh, well, the wins and, Oh, it was just absolutely brilliant. Um, he did the best part two hours nonstop, and I came out onto Charing cross road. I don't know if that fear her stomach crunch laughing so much. I just, I just knocked it. I know, I feel well. Wow. You know, I was rolling my eyes, which is, you know, fantastic. Um, I think he was, his anecdote will still accommodate, you know, the way you tell a story. And also those endless observations on even 40 bulls, um, that we all have. Um, it was a kind humor ultimately. I mean, he could be really Shawn. He was never on tokenistic, like a lot of comedians of his generation. And, um, you just heard the models, which one is sending up pump his figures of authority, which always went down well with me,

Speaker 1 00:34:31 Tony Murray, they're raising Dave Allen onto the plastic pedestal and making him his own. I shall content myself with Wogan. Now back to cherry Smith Jerry's cycle of poems, famished published by pin drop, press addresses the potato famine of 150 years ago. I asked her whether this is just old history or if the past is still very much a matter of the present for her.

Speaker 2 00:34:55 Yeah. Everybody says that about our limbs. This tree is ongoing. Well, Doug, you know, the thing that struck me long before 2012 was the idea that before the famine, we had 8.5 million people. Now we've got, I think six or 6.5. We've never made up that two and a half million at least to dive in the fall on that kind of cycle of, you know, unemployment recession migration. It just continues. And there were, there was moments during Celtic tiger where lots of people were going back. The less young people were leaving where it felt like, Oh, it's. But, um, I, I most, I mostly kind of, I was very shocked to learn that, you know, half the people who died in the farm on spoke Irish and, and, you know, or most of the people who died, spoke Irish and that, um, there were 4 million speaking Irish and the 1840s and after the farm on the Romy 2 million, so it had this huge impact on the language and the fabric of the culture. And I think we are still seeing the effects of that.

Speaker 4 00:36:12 That's something that really struck me with that with, with, um, with famished is, is the question about, um, what uses a language if it can't protect you from this? Uh, and that's the, um, the, the, the, the, the, the, the, the, the swathe that the family cut through the, the, the Gaeltacht area, um, and certainly where my, where my, where my dad's, um, family concerned. And they came from so very, very rural County Claire. Um, none of them spoke Kaylee cause, uh, and there's that sense, perhaps that you, you suggested there's a distrust of Gatwick after that?

Speaker 2 00:36:47 Yeah. Yeah, definitely. I mean, people told me this still that, um, they were embarrassed to learn Irish. They find it, um, backward, and they just put up with it. Um, one or two people who I asked to perform in famished and read the Irish translations, find that they were extraordinarily moved when they had to read it and re inhabit the language that they've so dismissed. Um, um, it was very important for me to ask, uh, our speaking poets to translate a few of the poems, because it felt like putting that cultural loss, addressing the cultural loss and, um, helping to, um, readdress it really. Um, I learned a lot about my own response to Irish, which always felt like I didn't have the right to look at it or speak about it because I didn't have any chance to learn it. Um, um, just working with, uh, the, the two writers for Cosby and Afric Mackay and having them around the piece and, um, um, ether came to nearly all the performances and read the, the field and Irish. Um, it was one of the most extraordinarily moving parts of the whole performance for me. Um, and just, just looking at the loss of indigenous languages and the vastness and the depth of what you're losing with, with these things. And, um, being very aware of what it means when people are picking it up. And even, even Protestants and Belfast are beginning to learn. Ours should be, it's just, it's a whole new Renaissance of, um, uh, den identity repair, I suppose you could call it.

Speaker 4 00:38:52 I noticed that it's like a, it's, it's two points in particular. It's a, they eat grass in the field that both get, um, and you put it in the, in the full ones, translated ones, trans created a what to do, ask what's a trans creation.

Speaker 2 00:39:04 Well, again, it's someone who wasn't very confident about her Irish. And she said, I don't know if I can do it. And I'm going to have a half to ask etymologists, and I'm going to bring out words that have almost been lost. Aren't used in our speaking anymore. And she really saw it as an archeological thing, um, where she was learning and she was interpreting it. And she was a little bit, you know, the word Garay is not a word that's associated really with fields. It's like a Connor Mara word for a little patch of land, the thing, or even a garden. Um, so she was a bit, yeah, even that thing about who's got the right to do it. She felt bad and she lives in the Gail talk and speak Saresh to her son, but she, she was one of those people who resented learning it and got away from it and then was pooled back. And, um, I, I just, I just find that all very profoundly moving and enriching to work with and think about,

Speaker 4 00:40:10 As you went through, um, your, your, your, your research, and we're also talking about, um, uh, language and loss language and so forth, that there's a sense of a lost history here, or a, um, a history that has been put to one side.

Speaker 2 00:40:23 Yeah. Well, whose history is it? I mean, it's a broken history, isn't it? Um, um, with that, then you get a lot of secrets and who holds the secrets and you, you have, you know, the survivors shame on the Irish side, on the survivor shame on the English side, um, you know, these, um, stories that the English don't know either. Um, I think it was that sense of making links with a broader global picture that, that allowed me to retell the history, um, in ways that could include, you know, Indian famines and, um, responses to Churchill, um, and those kinds of legacies that are sacrosanct. And just beginning to question and open that art was very important to me.

Speaker 4 00:41:17 Yes. Because one of the things that strikes me particularly with the third section is that this is a much broader patchwork than just an Irish story.

Speaker 2 00:41:24 Yeah, definitely. Yeah. Um, it's really looking, you know, someone said to me, if the farm one was, no, they are fish would be not allowed to come to England. We would be deported immediately and stop from London here. And I, I think, um, looking at the ideological structures of growing fascism, you know, it's the feminism model for, you know, what's, what's happening now with, with refugees and, and increasingly with the kind of elite ism that we thought we'd become to dismantle. And, um, you know, when you're excluded by it, by your skin or your accent or your education, um, you can really see how it works and looking at the, the rights of gross shooters to go out in their packs, um, while kids come play, you know, in a bigger group in the playground. I mean, I just, I just find the kind of continuing entitlement of the British elite, just, you know, profoundly shocking.

Speaker 2 00:42:35 And, um, those, those sort of repercussions, you can see it through throughout the world really. Um, um, I think you always think you're going to be ready for fascism when it comes and you're going to do the right thing. And then it creeps up in ways that you, you didn't even notice, or you felt powerless to question, or in this case, we were accepting so much because of the desire to protect each other. Um, but it's, yeah, it's very frightening to see what what's going to be, um, kind of solidified by these processes of disenfranchising people, which are going on every day,

Speaker 0 00:43:24 <inaudible> halo. So hemp <inaudible> have enough in all another extract there from the live performance of famished, by cherry Smith, with Laura concealer and ed Bennett, given the poets of reportedly solitary creatures. I asked her about the origins of this collaboration.

Speaker 2 00:44:01 I think the origins of working with collaborators was the sense that I didn't want to go out and read 10 minute extracts of farmers. It's not a poem that can be extracted, uh, very effectively. I wanted to read the whole thing, or I don't read the whole thing, but I read about, um, 45 minutes of it. Um, I felt like I wanted a sense of the collective, the collective performance, the collect of morning, because so many, so many deaths in the farm and weren't mourned. And so many rituals of deaths were dismantled from the keening to the, the wake. Um, and I, I felt it was very important just to process that together. Um, I'd worked with Lauren Kunstler on an earlier project, um, with her jazz group and she'd taken some other poems and put them to music. And I absolutely loved working with her.

Speaker 2 00:45:04 She's an extraordinary improvisational singer and she makes these guttural growling, gargling sirens. And I working with her, I realized that she could embody the blight itself. She could talk, speak through her strange, um, uh, improvised sirens and vocalizations in a way that words couldn't, and she could speak for the anger and the grief, and almost like the light talking to itself, um, which was just such a revelation to me and working with, um, at Bennett using, um, phone fragments of, of Saren from the sea or the wind, um, mechanical science, he built to Nat electronics score. And so that was able to, uh, draw out emotional contours if you like that, that open people up and kind of held them in a way that, just the words alone, perhaps couldn't. And, um, I, I just, I loved the fact that people committed to coming to sit and listen to, you know, a NARS length performance about the farm on, um, that felt incredibly special to have that chance to perform it in that way, um, to create a space. I had Q and A's after every performance. And that felt very important for people to say, we felt a silence. There was a silence in our family. There was a silence in the school. There was a silence in the university and to have a space to talk about it and to take the book and go off and yeah. Learn, learn aspects of our history again.

Speaker 3 00:47:01 And did the performance of that to take you back at all, to those family gatherings, where you would recite in 20 verses of poetry, or somebody would have a song and things like that, was there a familial element to it, do you think?

Speaker 2 00:47:14 Oh, of course. Yeah. And one of, one of my cousins who was at those events came to the one in Dublin and it felt, uh, like a circle coming Barnes. And of course when my family were there and the performance important Stuart, that, that felt, um, yeah, very, it was very holding and, um, yeah, it felt, I suppose, that I was fitting not only myself, but my ancestors into a much broader canvas of history and belonging that perhaps, um, being from the North on being from a Protestant tradition, you're maybe self excluded from that, or there are there ways in which people assume that you're not part of that history or not part of that suffering in the same way

Speaker 4 00:48:08 Let's come on to that because when you and I first met, um, you mentioned that you felt that, uh, you weren't considered authentic for reasons of coming from Northern Ireland or being Protestant, or indeed your own sexuality. Um, how does that manifest itself?

Speaker 2 00:48:24 I think that question of what gives me a right to do this is something a lot of writers and artists face. If you're a doctor, you don't ask that question, you fix the wounded body. Uh, if you're a writer, you don't know if you can fix it. You just going to describe the wound, what qualifications have you got to describe the wound? Well, you know, I lived through some of the wound, but I also left the wounded by going to England, or I left the expectations of a hetero patriarchal culture, or, you know, it's, I don't think it's particular to me, but I think, you know, an archeologist or scientist doesn't have to justify what they're doing, but often we do, um, that imposter syndrome, a lot of those successful writers have talked about that. So funnily enough, I think that perhaps if I'd stayed in Ireland, I wouldn't have felt the nerve to approach the farmland. A I might've thought it's all been done and B to talk about translation and transcreation of English into Irish. Perhaps these, these taboos of these Shibboleth are imagined or not as grand as you think they are. But, um, I think if you look at the writing George Bernard, Shaw, James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, home, many of them have to leave in order to have permission to do it. And, um, I, I think being part of a very international intercultural society in London, um, kind of gave me the strength to go back in my imagination on my language.

Speaker 4 00:50:17 It's interesting. You talk about having to almost go away in order to be able to get, if not perspective than permission to, or if not permission perspective, uh, to, uh, write about matters like the family and so on and talking to Tony Murray last week, he was saying about the time that you spent living in Spain and he can simply describe himself as Irish with having to go. No, no, I'm, I'm, I'm, I'm, I've got Irish parents while I was born in England. Uh, the, the lack of need to explain yourself.

Speaker 2 00:50:46 Yeah, absolutely. When I came to London, I was definitely Irish. I was stopped by the police and asked if I'd been drinking. Um, I was asked if I was a terrorist. Um, I was made fun of I, a lot of the, um, quotes in the book. Uh, Ryan, Dante Irish racism were sent to me in the eighties, uh, the, um, the Tate wit and the shape of the paperweight and the shape of a potato. You can boil this in the case of Carmen that was sold in an airport shop in England. Um, there just, there were just many things that I find, yeah, I'm much more harsh than I thought I was. And then when I went to, um, America, funnily enough, you know, I felt more European. I was really then the very identified as coming from Europe. And, um, there, as, uh, as I said to you yesterday, the, the stereotype was still there, but it was formed out of different things. Instead of being a terrorist of drunk, someone who was violent on controlled, you were a Saint or a scholar and had a fantastic eloquency. And I was like, well, I'd like this stereotype much more. Thank you. Um, so I find it really invigorating and, and, um, joyful to live in America for a few years. It was very good for me.

Speaker 4 00:52:14 It's interesting though, that the, uh, the, the, the, the, the, uh, super K plastic Patty is one, that's either applied to, um, uh, Irish or descendants in England or in America. Uh, and there are two very, very different relationships, but they're still both considered in authentic.

Speaker 2 00:52:31 What is that kind of judgment of the other that says you're not enough. Um, and I felt, you know, when I've met second and third generation, Arish people, and they're particularly with women, their married name, doesn't give it away. And I'm getting on really well with them. And I'm thinking, God, I just you're so familiar to me. And I can't believe it with that German surname. And then I realized they're married to a German, and of course their name is really a Cartney or O'Leary or something. But it's interesting that I would say I've a couple of friends who were brought up in the North who are more British identified than some of the second or third generation Irish people I meet here. So it's, you know, it's, didn't fentanyl tool wrote a really great book, maybe over 10, 15 years ago about, um, Irish identity.

Speaker 2 00:53:32 And what's it called green card, black hole or something like that. You'll have to look that up. I don't know what it's called now. Um, but he talks about, you know, who can say who's more Irish, you know, someone working in a bar in Chicago, who's third generation Irish, or someone living in the heart of Dublin, um, who, uh, can't wait to leave and go to Australia and, you know, leave it all. Um, so yeah, I, I think those, those divisive for identity troops are so limiting. Um, um, I wanted people to identify with famish to aren't an Irish or second generation third, but are just interested in har, um, suffering is manifested and dealt with what's the legacy of, of trauma and can poetry transform it. Um, if it transforms it, if they feel the empathy and they're transformed, and that's good enough for me, I did some reading into epigenetics because, um, I rad about the cycle kick scarring, and I thought, you know, how many generations does it last for?

Speaker 2 00:54:55 Um, they did really interesting studies into the Dutch famine that happened, I think just after the second world war. And they find that those children were primed for starvation and then have a much more of a propensity towards, um, diabetes, um, eating disorders on obesity. And they did a similar study with pregnant women during nine 11 and looking at how stress triggered their offspring. Um, I just think it's, it's absolutely fantastic, fantastic research, and it all kind of began to make sense to me, but just the other day, uh, I was listening to something and I thought, okay, so we've looked at genetic scarring and epigenetics with trauma, but what about epigenetics and ancestral joy? Aren't we all so primed for singing and dancing and putting her arms around each other and going, Oh, that's great crack. I mean, I, I sometimes, you know, tap people on the arm because I'm so moved and it, for us, it's a kind of come on then.

Speaker 2 00:56:07 Yeah. You know, you're a Mitt. And sometimes they do it with English people and they go, Oh, why did you hit me? I'm, I'm serious. It's just like the, the embodiment of my excitement is not misread in Ireland and it can be misread here. And I just find that so interesting that I've been looking at ancestral sham and ancestral pain and water boat, ancestral joy. And I enough, I feel like my first collection was a boat loss and leaving our London grieving. And the second collection, I just thought, I'm not going to look at that. I'm going to be drawn towards, um, exuberance reconciliation resolution. And, um, I saw those books as balancing those things in me. And maybe after famished, I am going to go and write something that is about the physical experience of joy companionship, the collective touch, uh, things that we're really defining an absence.

Speaker 2 00:57:11 Now, my final question is the question I asked pretty much every interview is about you being a member of the diaspora, mean to you. I suppose it's pretty tribal being part of the diaspora. I mean, I say that I left and I didn't look back, but my poems looked back, but that's not true. I'm always looking back. I'm always looking for a way to be back. Um, but keep what I've learned here with me. And I don't know if that I'm ready to do that yet, or I can find a way to do it, but yeah, I, I love that kind of exploded belonging, wherever you go, you'll find your Irish pub where you find someone who looks like your auntie VI and there's the kinship. Um, um, without being sentimental, I, I do cherish it.

Speaker 1 00:58:14 You've been listening to the plastic podcasts with me, Doug Devaney, and my guest, Jerry Smith, the plastic pedestal was provided by Tony Murray music like Jack to that find out more about us and subscribe at www belt, plastic podcasts.com, or you can find Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter. The plastic podcast is sponsored using public funding by arts council, England.