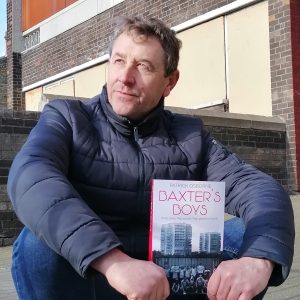

Speaker 1 00:00:22 How you doing? I'm Doug and y'all listening to the plastic podcasts, tales of the Irish diaspora. If you're listening just as this drops, as they say, it's a St Patrick's day special. If you're listening later, then I hope you've recovered from March the 17th 2022 is more than just a patron saints day on the centenary of the Irish state. No, it's also the day that across the water is published by north redox, press the second in the Liverpool mystery trilogy across the water. It's a sequel to under the bridge and sees Vinnie and Anne journey into Ireland to discover the true nature of Vinnie's father's. Death is an intriguing, fascinating book, dipping backwards and forwards in time to look at the diaspora of the 1970s. And it's a privilege to have its author Jack Byrne here with us today. So on some Patrick's stroke across the wall today, our first question naturally is Jack. How you doing?

Speaker 2 00:01:15 I'm fine. Thank you. Very good. Nice introduction. Thank you.

Speaker 1 00:01:20 So the book is coming out. How'd you feel about that?

Speaker 2 00:01:22 Hey good. Okay. I mean it's yeah. You know, it's, uh, it's the second book. So the kind of nerves and excitements are a bit lower down. The first one is the kind of big one, if you like. Uh, and yeah, it's a weird thing, you know, because, uh, people I know, so, um, I feel I'm quite lucky. A lot of people spend a lot of time trying to get published, fighting to find, uh, an agent and a publisher can take years. I mean, it took me one year and, uh, you know, I set myself a goal of starting to query agents and publishers. And if I didn't do it within a year, then I would self-publish, uh, because I'm not the youngest. And I thought, well, you know, there's nothing worse than kind of writing and not having an audience, you know, for me. And I dunno if it sounds vain or whatever, but there's literally no point in writing and no one reading it, you know what I mean?

Speaker 2 00:02:26 And so for the first week to be accepted and published by north rocks press, then obviously I was very happy. It's kind of, I hope you don't mind me going on, but it was kind of weird as well, because it was my first published novel. Uh, it was north of DOCSIS first book. So they're a new publishing company. And my agents based in Liverpool, I was her first deal of publishing deal. So it was kind of like a trifecta of W's and, you know, it's just one of those things just at the right moments. I think that's why I say I was lucky

Speaker 1 00:03:05 With this. Then you have that funny feeling of maybe the difficult second album

Speaker 2 00:03:09 And no, it didn't, you know, and partly well it's partly because one of the first bit of advice I got was that when you've written a book and you think the book is okay, you have to start counting it around publishers and agents start your second book, don't you, you know, uh, sit there waiting, you know, you have to keep writing in order to progress. And so I was well on the way, you know, but it sounded the first book was published and agreed and all that. Then the second book was well on the way. And, you know, I felt, okay, so there was no kind of stop period in between if you know what I mean,

Speaker 1 00:03:50 It was writing a, a time ambition for you.

Speaker 2 00:03:52 It's always been in the background to be honest. Uh, it's always been present, uh, in my consciousness, the story I tell, which is true, uh, when I was 16. And I remember back in, uh, you know, the counselor's bedroom and speak, and I started trying to write a biography of my dad and my dad came across from Wicklow after the second world war to Liverpool. And he was a painter and decorator and it just a normal working guy. And I wrote about half a page and I didn't, you know, I didn't know what else to write basically, but I had that edge, you know, to, to tell that story. And funnily enough, I think under the bridge, you know, however, 40 years later, it's kind of the culmination of that project because although it's not, you know, the story of my father is the story of my father's generation. So, you know, after the second world war, the tens of thousands of Irish people traveled across to the UK to help rebuild the country, staff, the hospitals, you know, nurses, teachers, as well as the novelties and brickies that we all know about. And, and yeah, so it was kind of, even then, I kind of knew there was a story to be told, but I didn't know what the story was.

Speaker 1 00:05:12 What happened in those intervening 40 years for you

Speaker 2 00:05:14 Full life life, the world and its consequences? Um, I didn't, well actually I did write something, but that was about, I don't know, 30 years ago now, uh, basically I left school with no exam results. Uh, I didn't even set an exam, not even the CSEs or GCCS as they were at the day and then all levels. So I left school completely unqualified, and that was partly a conscious choice. And I know that sounds crazy, but I went to a grammar school for the first three years of secondary school, a Catholic grammar school in Liverpool, one the best in liver pill, not the best, but one of the best. And I just didn't take to it. And it didn't take to me. And it was a working class kid from the council of states, semi dad was a painter and decorator. And I was largely in the company of sons, of them, accountants and lawyers and executives or whatever.

Speaker 2 00:06:14 And, you know, I just didn't fit. I didn't fit there. It didn't fit me. And so I left after the third year and I didn't get expelled. I, you know, you have this thing did them. We had to go in to see the, uh, the headmaster, the headmaster was at cannon, can't remember his name, but you know, some parts of the hierarchy in the Catholic church and went in and said, okay, next couple of years, the big year start preparing for your exams, what you're going to do. And I said, I'm going to leave. And he said, well, let me see where people are selling me. I'm lucky I am to be in privilege. Well, let someone who's going to enjoy come cause I don't want it anymore. And so I left and then went to the local, secondary modern school, left out without any exam results and went into the world of work.

Speaker 2 00:07:02 So, and then I worked in factories often down around the country. I left till one was quite young, moved around working. And, you know, eventually I was in Manchester in kind of late in the nineties I think. And I wrote a novel then, uh, but I, you know, I didn't have the money to do anything with it or the contracts and publishing, you know, it was, you know, it's about that thick, it's probably on the shelf next to me. And, you know, even just faulty copy in it in those days and sending it out would have probably took a week's wages, you know? And so I didn't have the resources to do anything. And then, so I'd left it. And then many, many years later, uh, I started writing again. And in the end I went to, uh, eventually I went to the university of Houston when it was for two years old and did a degree. And, uh, so then that renewed the interest in writing. I went there because I wanted to write, but I didn't feel, I knew exactly how. And, uh, to be honest, the university didn't really teach me either, but you know, later on, so it's always been present for me. I think that the desire or the needs, right.

Speaker 1 00:08:23 I saw you with a, an interview, uh, where you said that Irishness had been educated out of you.

Speaker 2 00:08:29 Uh, yeah. So the headline, you know, editors pick the headlines and I don't know if I, I mean, I might have used those words, but thinking about it, reflecting on it, it's kind of a bit different. What I said was true. You know, I went to school in Liverpool, Catholic school, both Catholic schools, grammar than the local second remodel. And, uh, Liverpool is one of the few places where education is actually segregated. So you have state system and you have Catholic skills and kind of every district and every area. And it's known as Protestant Catholic skills, even the one in the states. And there was a kind of deal made in the 1830s, whatever knows lights now, but the late 18 hundreds between the council and the education authorities when skills were beginning to be settled. And one of the stipulations was Catholic schools could run the school.

Speaker 2 00:09:22 Catholic institutions could run the skills, but they have to stay clear the virus history. And, you know, even when I was growing up in the 1970s, Ireland, not just as a subject, but literally, I can't remember anybody speaking the word in geography and history and any subject, it was just, you know, uh, it's a kinda overused phrase, but kind of ghost in the room. It wasn't mentioned even though, you know, Catholic skills, 90% of our parents were directly first or second generation Irish. And that was just weird, you know, but it doesn't hit it's a later, you know, so it wasn't educated out to those, if you like, it was just kind of amnesia. I've heard a guy called Joe Qur'an, whose name is, and, uh, is an academic originally from Ghana. And he had this poker, I can't remember the title, but it made a lot of sense to me and not the whole colonial period and the whole empire.

Speaker 2 00:10:22 There's an amnesia about it. It's not so in British skills, it's not. So, you know, she's kind of glossed over and assumed that we were parts of this world community with no details of how it happened or brought about what the facts were, what the consequences were. And I think that was true in relation to islands as well. And you can, you know, it doesn't take a lot to realize why they don't talk about Ireland in English skills, because where do you start and what you jump over in order to explain the relations between England and Ireland over the past hundred years and more so a long way of going around it, but saying that, yeah, I grew up dad was directly Irish. All my grandparents were Irish. My mom was born in Liverpool, but both her parents were Irish. And because there was no Irish culture in our house, then, you know, it just didn't register with me. And so much later

Speaker 1 00:11:23 We grandparents were from

Speaker 2 00:11:25 Whitlow. So all my four grandparents were from Wicklow to south of Dublin.

Speaker 1 00:11:30 And you're in Liverpool, which has a high incidence of, of members of the aspirin, things of that. And yet you're saying there was no Irish culture in your house?

Speaker 2 00:11:37 No. Uh, well, unless they're the Clancy brothers in the bachelors, in the, uh, the, the records and my dad's a stereogram, that was the closest, I think we got to it, uh, partly, you know, I grew up in the seventies and, you know, okay. Maybe for younger people, it's a bit hard to understand, but in the 1970s, there was two ways that you heard about Ireland and popular culture. One was Saturday night comedians telling you how stupid the Irish people were, the Englishman, the Irishman, and a Scotsman was the formula for a joke. And the Irishman was always the stupid one in the joke. And that was regular Saturday night TV. The comedians is on the biggest shows on TV at the time. And then you had made a and bombs in the 1970s in the north of Ireland, and they were the two kind of frames through which, and richness was kind of a recognized, I think, or kind of around in the culture.

Speaker 2 00:12:42 I mean, you had some of the things about doing a kin as well. You had the, you know, and so you had the kind of old home welds kind of island, but then you had the, you know, which looking back, there's no other way to say it, but kind of extreme racism of the Saturday night comedians. And you had the constant news beats, the drum beat of the struggle in the north of Ireland. Uh, so in my house there was no particular Irish culture. My dad was where her money when I say work painted mainly in industries. And I know, you know, speaking to a lot of older people that it wasn't easy to be out and loud and proud of being Irish in predominantly, you know, English workplaces. So in the 1970s, there were times when the demonstrations of car workers would leave the factory lines in Rover and go out on the streets against the IRA after the Pope bombings and so on.

Speaker 2 00:13:41 But imagine being an Irish person in that situation, then, you know, there's a pretty heavy blankets over, uh, the expression and the culture of Irishness. I think, I don't know whether that was the case with my parents. So they just went particularly cultural people. You know, you know, the book, there was no one around me when I grew up and it wasn't just me. It's like, I know that where some families, you know, uh, especially around the north end of the city, because the old Dinesh community was in the north end of the city after the second world war, lots of bombing and so on. And the neuro states were built around the edge and lots of people were moved to these newer states, which had much less, uh, culture of the inbred or developed culture. If you like from the old Irish community based around the north end of Liverpool, which did have its cultural clubs, which did have, it's kind of, you know, uh, it's culture, but in the states, uh, you know, like the one I grew up on there was very little of it. There were Catholic churches, the social club connected the church, but it was Catholicism, not Irish.

Speaker 1 00:14:54 I was, while I was going to ask, cause I was essentially, that's like Catholicism became almost like a euphemism for being Irish.

Speaker 2 00:15:00 That's right. Yeah. And it's still, it's just some degree, isn't it? You know, people kind of, you know, uh, Catholic in Liverpool meant that you went from owner's stock. Uh, but yeah, the education, the culture was Catholic rather than Irish.

Speaker 1 00:15:21 You're listening to the plastic podcasts. We all come from somewhere else, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, while he may not have been surrounded by Irish culture at home, Jack Burns novels reflect the man's fascination with diaspora history, particularly in his home city. And this second part of our interview, we talk the surprising tale of St Patrick's day parades pool. But first I want to know about the title of his first novel, where exactly is under the bridge.

Speaker 2 00:15:51 It's a place called Garston, it's a community next to the dock. Uh, it's the most steadily dock of the Liverpool dock system, which is seven miles long. And it's more subtly of dam and it's under the railway bridges, access to the community is very tight-knit small community. Uh, and so it's called under the bridge. It was actually known partly as little flow because they wanted the, you know, the same anywhere I guess, and immigrants and immigrant communities. You get one family move over and then a brother or sister and a cousin and a friend. And before, you know it, you have a little anklet wave of people. Well, my grandfather was from, with low is a seaman. And, uh, this is my mom's father and there's a shipping trade, regular trade between will clone Gaston, lots of timber and bricks and other things, but, you know, coming in and outs of the docks and my grandfather moved from workloads and Liverpool to Garston to start shipping out of Garston through Garston docs.

Speaker 2 00:17:04 And a lot of other people did the same. And so under the bridge is known as little, little workflow, but it was also, you know, uh, an English community as well. We had the little Westlow parts of it. In fact, it's really weird in some senses because there's a streak of window lane under the bridge. And on one side of it was recognized as the kind of Irish side. And the other side of that lane was the English Protestant side. So it's weird even geographically, you know, the areas took on the kind of the divisions that were much broader in the city, in culture and politics.

Speaker 1 00:17:43 And what was it that spurred you on to, to, to writing this particular story then

Speaker 2 00:17:49 Under the bridge follows the fortunes of two, uh, immigrants from Ireland to Liverpool and they're in the dock area. And it was to explore that experience of arriving in the 1950s and the opportunities that were available or not, and open the people and the two main characters enough period that the parts of the narrative and take very different courses if you like to integrate into life. I mean, won't, they both start off attached to a kind of criminal gang next to the docks. One of them, uh, you know, it has enough and he gets jobs, he gets job in a factory. He gets a job and to build a science, you know, and it's the kind of, I want to show some, some parts of the reality, but within this context of the overarching story of Ireland and the relations between the two countries and how that affects them living in the seventies and eighties and nineties in Liverpool in the UK,

Speaker 1 00:18:59 But you've also got a third timeframe haven't you? Which is psych a 2010 or thereabouts.

Speaker 2 00:19:03 Yeah. Okay. So yeah, there's in the, in the first book on the, the bridge, there's the fifties narrative, which goes up to 2010 and there's a constant 2010 narrative. And in that one, there's a Anne and Vinny and as a young reporter from Liverpool, uh, she's mixed race, uh, uh, young woman. And she's a new reporter and Vinny is, uh, is from, you know, under the bridge and I'm from speak and his father was Irish, but didn't know Ronan. So he doesn't really know about that and he's in university and he wants to do a master's degree and he wants to do it on the story of immigrants from Ireland to the UK, partly, you know, just so he can understand his world, but as they get into the story of bodies discovered near the docks and begins to investigate, and then they start uncovering this history of the Irish community near the docks in Liverpool. And it begins to impact on, uh, on ventings life.

Speaker 1 00:20:11 The Irish are often known for being psycho remembering and in remembrance. And I wonder if that you think that's as part of the culture that you might have inherited whether or not there's anything around you, apart from and the Clancy brothers That perhaps that like the past is always with you.

Speaker 2 00:20:26 I don't know. I mean, you know, it's, it's kind of part of it, I guess. Uh, it's funny because you know, the little pill capsule of Ireland, you know, many people say and, uh, the St Patrick's day parades, you know, there's speakers coming out or St Patrick's day have been St. Patrick's day parades and Sydney and New York and Chicago, and you can watch them on the telly and in the river green. And there's tens of thousands of people in Liverpool that isn't, uh, they were, they didn't exist. They didn't have an asshole until 2012, I think was the first resurrection. And that one was kind of, uh, pushed off the streets if you like, because, um, you know, EDL and right-wing were calling it, uh, you know, uh, a nationalist demonstration of support for the IRA. And it was literally people wanted celebrates in Patrick's day since then.

Speaker 2 00:21:23 It has happened about three times, I think, before COVID, but the very small affairs and people are trying to build it again. So it's kind of like, you know, memory or not memory, you know, these stories exist, but not publicly celebrated. And I think it's possible to do that. Now, there are many more Irish bars, for example, in Liverpool than they ever were before. Uh, and so I think since the, you know, the peace in 1998, good Friday agreements and so on, and Irishness is allowed to be, you know, celebrated and looked at again. And I don't know, maybe, you know, I'm a part of that movement as well, you know, consciously or not, but, you know, we're all affected by our surroundings. And so I think that might be part of it. You know, one of the things is, uh, caring more, if you like for me, is the, uh, the kind of relationship, although not always public and not always open and not always celebrated between the communities that exist in the UK exist in Ireland, exist in the north of Ireland and the kind of links and connections that have always been there, even if not publicly celebrated, you know, a lot of our families were from Ireland.

Speaker 2 00:22:46 Some of them went back often. Some of them didn't go bash it. So, but within those, those connections exist, you know, the Michael D. Higgins presidents of the Republic, uh, said, uh, between, I think he said between, uh, I think it was the end of the second world war, 1970s, uh, something like four to 5 billion pounds was sent back to Ireland from people working in the UK and abroad and kept the Irish states of floats was how he put it, you know? And so it's like, you know, if you travel around Ireland, there isn't an Irish family who doesn't have a connection and uncle or brother or cousin who went off to the UK or to America. And so, you know, I have this thing now, that's just in my head that the ebb and flow of the Irish sea, you know, it's not a kind of, it's a bridge rather than a disruption, if you like in a geography and it brings and take people back and forward. And that has been going on forever and will continue on it's still going on now.

Speaker 1 00:23:58 And yet Liverpool for a long, long time was quite divided given the fact that it was also the home of large number of orange marches.

Speaker 2 00:24:04 Yeah, it was a 1974. There was a Protestant party stood in elections and had counselors of till 1974 in parts of Liverpool. There's a real, uh, history of that division. Uh, you know, now people see Liverpool as a kind of basket of labor and red and so on, and it was conservative for most of the 20th century. And then it moved towards liberals in a kind of seventies. And it was only later in the eighties and nineties that you start to getting labor elected. And the reason it was a conservative was unionism that Protestantism was central to the power structure in Liverpool. And, you know, all the counselors were Protestants, you know, in the 1920s, you started to get a bit of a breakthrough in the thirties and forties, but for long periods is dominated by conservatism and unionism. And although the field is a very working class city, that was how they could do it because unionism presented itself as the defender of the English Protestant working class.

Speaker 2 00:25:17 And, you know, they were able to do that. And parts of Louisville, the north end had the, uh, an Irish nationalist Stampy in the house of lbs of, to the 1920s. Uh, and so those divisions were very real and the, you know, the violence and all, you know, all I can stop and the orange March has gone to the state, largely peaceful. You know, they get the opportunity to celebrate and March with sound sensor, they'll get on buses and trains and go onto south fourth. Well, yeah, it's a husband. I think it's kind of diminishing now, but it has been a huge part of the history of Liverpool.

Speaker 1 00:25:56 One of the things that interests me and always does about being a member of the diaspora, the diaspora in general is that there's a division there, or there's at least a dichotomy, which is that the diaspora in England, I have a foot in two countries, but I haven't home in neither the way that you're describing to the policies that's made manifest as well. It's not just simply the capital of Ireland, but it also has the same divisions and contradictions the individuals from the diaspora also have.

Speaker 2 00:26:20 Yeah. And, you know, it's kind of, uh, it's, it's weird because, you know, my family's history is my family's history and it's not invented or made up, but it's not every family's history. Do you know what I mean? And it's very hard to speak in all, you know, in general for everyone, but there are certain overlying facts, which are true, you know, about the education system, about the lack of, you know, Irish participation in about the elections, about the presence of the orange and the Protestant party of, to the seventies. But within, you know, within some places, people did keep celebrate their, their Irish culture, you know, throughout all that difficult period. But it was an end claims. If you like, you know, in small parts, maybe in the local Catholic club, they would run an, I understand in class as well, our Catholic club bins, but, you know, some did, you know, I know one or two that did, so it's a real kind of mixed bag, but in terms of public perception, yeah, there is a distinction.

Speaker 2 00:27:28 And I think people do find that quite weird, you know, because, you know, I mean the government, the, uh, you know, the counseling of the pill and everybody now celebrates, you know, uh, it was city of culture in 2008. And the slogan was well in one city, which is a lovely, lovely slogan, but you ask, you know, the black people and the Africans and system degraded the Irish, you know, they didn't want us in a city and the active attempts to drive people out to sit and stages. And it's kind of like, you have to recognize the past as well. You can't just jump, skip a beat, jump over it and say, well, we're all happy together. Now we can all, you know, wave whatever multicolored flag and whichever one we're celebrating at the moment. And isn't it lovely because things don't disappear. So simply

Speaker 1 00:28:28 You're listening to the plastic podcasts, tales of the Irish diaspora also available on Spotify, Amazon, and apple podcasts. Normally at this point, I introduced the plastic pedestal where I ask one of my previous guests to talk about a member of the diaspora of personal cultural or political significance to them. However, as this is a special, I thought I'd do something different and introduce a favorite outtake on occasion. A guest has so many stories. It's just not possible to fit them all into the running time of the podcast. Sometimes something has to go, and this is one of those somethings. So for the next five minutes, enjoy the tones of Nathan Mannion curator at epic, the Irish immigration museum, as he tells the tale of Nellie Bly,

Speaker 3 00:29:14 Um, Nellie Bly was the granddaughter of an Irish immigrant to the United States. Um, but she, her really am, um, was Elizabeth Cochran. She had an interest in becoming a journalist. So she wanted to really make a name for herself. She adopted the alias Nellie Bly best and a popular song, but she was one of the kind of pioneering investigative journalists, um, in New York. Um, and really in the world, she got a job with the, with the New York worlds working under Joseph Pulitzer, who the Pulitzer prize is named for, but he wanted to heart to focus on kind of sensational stories, popular stories that would boost readership, which is something obviously everyone's familiar with today, but she took it. She went above and beyond. So one of her most remarkable stories and one that gained her kind of my status as a minor celebrity, she faked insanity to.

Speaker 3 00:30:03 So she would be committed to a women's lunacy asylum on Blackwell islands in New York. So she could report on conditions in there. Um, and the, the, how she did that was remarkable. She talks about going to a halfway boarding house in the city, um, kind of making herself stay up all night. So she'd be a bit better idols and a little bit out of sorts and acting a little bit strangely so that they would call, um, uh, policemen to check on her, the policemen, she obviously acted so convincingly. He believed her. He took her to the local judge, um, who again, basically decided that no, she was definitely insane and she had no one to watch for. And, uh, they committed her to the asylum. So she went in under the understanding that Pulitzer would take her out after a few days that he would vouch for her.

Speaker 3 00:30:50 So that's a lot of faith in your employer, to be honest, I must say, but she was there. She said that the conditions were appalling. The doctors were negligent. And, um, the staff mistreated a lot of the patients. They were deprived of water. They, many of them were screaming all night just for a drink of water. They were overmedicated. Um, sanitary conditions were, are atrocious. And when she was released, luckily did come get her house. Um, she wrote the article, um, and it became a sensation that led to a grand judicial inquiry. And the entire system was reformed as a result. Um, but that's not what she's best to remember for interestingly enough, you think that'd be enough. She was a war correspondent. She went into orphanages, tenement buildings, the kind of plight of the working class and people who were less well-known. She would always champion them, usually in disguise, she'd go in, inspect them, write it up and, you know, bring about societal change.

Speaker 3 00:31:37 She was the correspondent in the first world war, but she's best well-known for attempting to break the records set by just runs FIC, fictitious videos, fog around the world. In 80 days, she came to Politan said she wanted to try and break it. Um, herself, he backed her. He said, yeah, you can do it. This would be a brilliant material for the paper. It was sell hundreds, thousands more copies than, than we would usually, and we'll pay for it. So she took off, um, to travel around the world to break that record. She met Jules Verne when she was in France, he left from New York, she traveled via via England. She went to France, she traveled down through Egypt and she traveled down through Srilanka and on towards China to Japan and eventually back to, to San Francisco and across the United States. And, um, it's a really compelling story.

Speaker 3 00:32:27 The rival newspaper cosmopolitan actually sends someone in the other direction when they heard they were doing this to try, beat them, to, to steal their thunder. So she had a rival traveling against her, which he didn't know about until the very later stages of, of the, of the race. She would report back by telegram sheets and dispatches from wherever she was back to New York. And they publishes, they made a board game, which they released in the broadsheet track. So you could follow her journey as well. It was kind of like a snakes and ladders kind of thing. Um, it became a huge sensation and there was definitely a bit of skullduggery as well, which was, which was quite interesting. Pulitzer obviously, uh, was determined that that they'd win. So she arrived back in San Francisco, four days behind schedule. He chartered a private train to take her across the U S so she wouldn't lose time.

Speaker 3 00:33:14 Um, he bribed all the station operators along the way of bottles of champagne, magnums of champagne, so that they could say, let the train true priority prioritizes, and then on unconfirmed, but potentially, um, as her arrival, Elizabeth was about to leave from south Hampton aboard a very fast transatlantic ship. Um, she was running a little bit delayed and they'd asked with the whole of the ship for her. Um, they didn't and people said that maybe he offered a bribe. She ended up then having to go to Ireland and leave from, um, aboard the Bosnia, which was a much slower ship. And she arrived back four days behind what she should have been. It was a very closely wrong thing. So she hadn't made that shift. She might've won. Um, but yeah, in the end, uh, blade broke the world record the fictitious one. She arrived back in 72 days. So by eight days, she beat that record.

Speaker 1 00:34:03 Nathan Mannion there. And if you want to hear more of our interview with Nathan or any of our fine fine guests, then go to our

[email protected] while you're on the website, why not subscribe simply pop your email address in the space at the foot of the homepage, confirm your details. And all the lieu to the diaspora world will fall directly into your inbox every time. Now, back to Jack Byrne, even on a day of celebration like this, we're aware of the unresolved conflicts raging through the world around us, inevitably Ukraine is in our thoughts, but we also concentrate on matters near our home past present and future.

Speaker 2 00:34:45 That's the point I was making about that amnesia thing, you know, like I said, it's all right, everybody celebrate now. And we've the, you know, the, the right colored flag and everyone's happy, but that only exists as long as the kind of the piece exists. If you like that you applied pressure to that. And it breaks apart along the old fault lines, if you haven't found a way to breach those fault lines, if that makes sense. An example of this, uh, from, you know, now, if you like, is the danger that Brexit and this, uh, you know, article 16 thing represents a Northern Ireland. You know, you had the good Friday agreements in 1998, you had peace, uh, you know, since staff, you know, but 20 years, uh, and it's not perfect by any means, you know, is the absence of direct war on the ground, which is a boon and a bonus to everybody.

Speaker 2 00:35:46 But unless you, you know, begin to examine why and how, what divided the communities, how can it be in communities actually be, you know, together and have a common purpose and a common plan. Then it's kind of, it's a veneer of unity that can be shafted. And, you know, there are people trying to Shafter that unity now around article 16 and the whole Brexit thing, you know, for other purposes or for their own purposes in Northern Ireland. So do you know what I mean, if you don't examine these things and if you don't, you know, work out well, isn't the interest of the majority of people and work for that, then you risk everything. Fragile pieces is, you know, I think, uh, a danger.

Speaker 1 00:36:34 Do you think that the, your parents not having that kind of a cultural investment in Ireland at home and so forth was a way of actually just maintaining a kind of peace there

Speaker 2 00:36:45 For themselves in their community? Uh, yes. Yeah. You know, they, uh, they, they been living in England in the 1970s, you know, I mean, I remember my dad telling me one point, you know, little story, how, when he first arrived, I think he arrived before the end of the second world war. And, you know, he would sometimes be accosted on the streets and called the coward and so on. And he's like, well, I'm from Ireland. It's not my, it's not my war. You know what I mean? And, uh, and so it was, I think for my dad and for my mom who was born over in the, the pill, it was a, you know, an ever present consciousness of who they were and where they were, if that makes sense.

Speaker 1 00:37:37 Yeah. I wanted to get some context there. So you say that your mother's father, your granddad on your mom's side, uh, he was a sailor. And what about the other grandparents?

Speaker 2 00:37:46 Yeah, on my dad's side, don't know that much, to be honest, I don't really know that much. I never met smuggling my older siblings Macedonia. Um, my dad left islands when he was kind of 18 or 19. Uh, and we went back once. I think when I was five years old, we took me dad back when he was, you know, much older, um, many decades later, but there wasn't a constant flow back and forward, and my dad never really spoke about his family and needed that mini moment either. You know, it's kind of like, I dunno, you know, the generalities about Irish, you know, the storytellers , well, it's not true for everyone, none of these generalities overall, you know what I mean?

Speaker 1 00:38:36 Did you have any aunts and uncles on either side?

Speaker 2 00:38:39 Yeah,

Speaker 1 00:38:39 Well they, over in England or

Speaker 2 00:38:40 Liverpool, we did have family in Ireland, but we just didn't know them. Uh, we went back when my dad, uh, was about, I dunno, 70, but it was well 20 years ago summit now. Uh, and we took me dad back to Ireland and my dad was a bit embarrassed, a bit nervous, I think, a bit afraid about what would well he would find or how it would be received, but actually, you know, it was really good and, you know, load, the people send off a local pub and it was a big nights and, you know, everybody had a great time with that. Loved it. Do you know what I mean? It's so it was kind of like, and we do still have family, you know, uh, quite a lot of family there. Uh, I've now mass, a couple of times, I've been back a few times for, you know, as, as you were grown up, we didn't communicate with them.

Speaker 2 00:39:29 Maybe I felt a bit embarrassed about it in the past that my family didn't connect to Ireland in a way that, you know, you look at other people and they do, and you think no one didn't mind, but I think, you know, a lot of people didn't, and there's a reason for that as well, you know, across the water. The second booth, one of the characters from Liverpool goes back to Ireland in the mid 1970s and is not happy to be back in Ireland. And he says, why the bloody hell do you think I got out? You know, the place is terrible. This is poverty, lack of options, lack of opportunity, and the overwhelming kind of burden of the Catholic church. And so, you know, for quite a serious number of people get into the UK or London or Birmingham or wherever was this idea, let's go make our fortune. It was like, let's get the hell out of here. You know? So not everyone was, uh, had that kind of, you know, glassy-eyed rose sense of glasses view of Ireland because they lived in it. There was a lot of poverty, a lot of social oppression, if you women, you know, there's lots of stories of, you know, young women who come across to the UK because they fell foul of the Catholic church, you know, in one way or another, because things are so restricted. And that's also a part of our, you know, heritage.

Speaker 1 00:40:54 How do you feel about St Patrick's day? The way that Irishness has almost become an industry?

Speaker 2 00:40:58 I mean, I think it's great, you know, I think you should be celebrated and get out, they wave the green flag, drink some guests. Why not, you know, fantastic. Let's have more of a, uh, so, you know, all for that, you know, a public celebration, uh, of Irish within the UK and within England, I think is long, long overdue. So don't have a problem with it. The fact that it can be reduced to a pints of Guinness and a big green hats, you know, that's kind of, but that's the commercialization and monitorization of everything that happens these days, you know, but it will allow hopefully the cultural space for people who want to, to dig deeper and develop more culture and more links. Do you know what I mean? And I think that's happening anyway, since the good Friday agreement is kind of that I think, you know, there's lots of, uh, young Girish people across in Liverpool, uh, either looking for work or studying or, you know, whatever brings them over. And there's a much more public, uh, expression of their identity, which I think is a great thing.

Speaker 1 00:42:08 We started off before. I sidetracked us talking about family, looking in the, uh, the interview that I cited earlier. You talk about your brother and his suicide, but I was wondering if we could talk briefly about that because your, your brother joined the army, didn't he?

Speaker 2 00:42:21 Yeah. Uh, I guess as a bull soldier, I think that same was at the time. And I honestly don't know if he was 16, 17, whatever, when he joined, you know, that's, uh, not clear for me. He was out in the far east Hong Kong for a period, you know, and I remember that they brought back, you know, he brought back, um, you know, those carpets with the pictures woven incident. And we had one in the living room, uh, you know, for years, for decades after the big stag in the middle of it, it looked really plugged in really nice and really, but, you know, it was, it was that kind of thing. My dad sent the football, I show outs every week, uh, from Liverpool with evidence results, uh, and sort of the staff, but yeah, and then after his period in the far east, they were stationed to dairy and, uh, this would've been 1974. And so things that difficult, 74, 75 and, you know, I mean, well for younger people who don't know that was the height of the kind of, uh, military national struggle against the British troops in the north of Ireland. And so he found himself in the middle of that and, uh, eventually took his own life.

Speaker 1 00:43:49 And how do you find out about that

Speaker 2 00:43:52 Coming home from school? One day curtains were closed and, you know, there's cars in the streets and we're normally cars in our streets. There wasn't a lot of car owners and, and you know what I mean, all the sisters come through and at that time, um, publicly it was, uh, an accident was how it was explained. So it was accidental and it was only many years later. Uh, I think when, I don't know, uh, in the nineties, late eighties, uh, I applied for the coroner's report and read the inquest reports and the coroner's reports, you know, and the verdict was what it was. And so it wasn't accidental. And so, yeah. You know, but yeah. And so, you know, maybe it's talking to Elliot about Irishness, you know, in our family, in particular after those events, then, you know, Ireland was the place not to be spoken of for many decades because of the emotions associated with it. I mean, I know my parents at the time for tooth and nail to stop and going, but, you know, he, he was what he was, you know, as a young lad wanted to get out of left field, join the army. And that's what people do, you know?

Speaker 1 00:45:18 And when you were being interviewed, you, you said that you felt that it was that he couldn't take the notion of being, being in Northern Ireland and possibly,

Speaker 2 00:45:29 Yeah. I don't know, you know, you know, uh, I was 15 and he was 19, you know, when it happened. So I don't know, you know, what was in his head more than any more than anybody else's, but it doesn't take a genius to work out that, you know, you have an Irish name, you can't live in the British army, you know, than Ireland at that time, you know, and the streets, you know, I don't know if you've been to dairy, uh, but the bog side, uh, tight tenements rope on row, tenement houses look very much like Austin, you know, literally, you know, if you took the street names off, you picked someone from the middle of one street, put them in the middle of the bulk side, except for the fact that it's silly and under the bridge is flat. You wouldn't know where you were, the names, the faces, the people with the same as the ones that he grew up in and on the moon. And that must be enough to bring a crisis of conscience to anybody, whatever else is going on.

Speaker 1 00:46:40 You listening to the plastic podcasts, tales of the Irish diaspora. We all come from somewhere else, not just somewhere, but sometime I'm privileged. The Jack's taken the time to talk with us, especially with the cross, the water coming out today as a trilogy of books. I wonder if the livable mysteries are a way of both dealing with the loss of his brother and reclaiming his heritage.

Speaker 2 00:47:03 It's partly that, but it's partly that, uh, not, you know, I don't want to sound like, well, it is what it is. It's not just me understanding it, but I think it's a story that's not sold enough, you know? And that's the part that I want to play. That's what I want to do, you know, with these three books, you know, I want to tell the story, because I think it's a story that is not that well known for all the proximity of England and Ireland for all that every city in the UK has, you know, a third that 20% of its population and some places 50% from Ireland, it's still not a story that is publicly acknowledged. And so that means that young people who've grown up today are lessons or Judith. Then I was when I was growing up and I think that should be addressed and that should be fixed.

Speaker 2 00:48:03 And I don't think it's just me just, uh, let me say this one thing about, uh, you know, this thing of kind of rediscovering your Irishness as an adult. Uh, if you'd look at the most famous product of Liverpool, the Beatles, you know, they, you know, international stars, all the rest of the biggest band in the world, what happened when these guys reached their thirties, you suddenly go, you know, after the, well, when the, the top 10 and the source of the American, so you get Paul McCartney releasing a song about Ireland, the violence, but then she gets on Lennon, exploring his own Irish roots and releasing a song about Ireland. And, you know, that's not, uh, it's not a coincidence it's because I think this is a process. Many people go through that. They begin to realize what they have missed. You know, that amnesia in society is it's not an amnesia of individuals.

Speaker 2 00:49:05 I didn't forget it because I was never told that just like, you know, Sean Lennon and Paul McCartney, didn't forget, it, it wasn't a part of their lives until they had the luxury and the freedom and the resources to begin to look back, where am I from? You know, how did my family end up in Liverpool? And, you know, do you know what I mean? And so for me, the three books apart, parts of that, there's a, an incidence in the second booth. Uh, I'm not gonna, I'm not going to give it out now, but it's a shocking incidence right in the middle of the booth. And it's a turning point for one of the main characters. And it is a truth that is not spoken enough. Uh, there's a campaign in Ireland called justice for the forgotten. And it's the forgotten victims of, uh, bombings that took place in Dublin in 1974.

Speaker 2 00:50:02 And most British people, no idea about this, you know, no idea, no idea is even possible or, you know, certainly British shouldn't be involved in anything like that. Come on, you know, and, you know, the story deserves to be told. I think it needs to be told, you know, the governments have recently passed legislation saying that, you know, members of the security forces cannot be convicted of crimes for sheer joy on the course of their duties. Really? No, really. And why now, because there have been families fighting for decades for justice around these questions. And so yeah, they, they want to shore up the edges if you like and make sure that the, the, you know, the truth of some of these events lays dormant so hidden, and it's not saying about, you know, okay, so celebrating Irishness, no problem with that, go ahead. You know, all for it, but let's subsume honestly about the whole relationship and, you know, that's on all sides.

Speaker 2 00:51:06 You know, I think nobody claims, you know, that, uh, there are angels or people who've actively fought against the British states and nobody claims to went mistakes made and innocent people killed. I haven't met anybody who says that, except for those who say that all the blame lies on one side and that's just ridiculous. It doesn't take a genius to work. That's not true, but how did you find out about it? And, and so I hope that these three bits, yeah. I hope to stimulate some people to go back and look at certain events and say, you know, could this be true? Is this real? So for me, that's an important part.

Speaker 1 00:51:48 It begs the question. How did you find out about it?

Speaker 2 00:51:51 Because I've always been aware of, uh, uh, you know, from those events, you know, uh, with my brother, uh, it was a conscious part of my life. We can't avoid it. Even if for decades, I did avoid the emotions connected to that and to the details around it, uh, you know, which is very hard even decades later to deal with. And, you know, my parents never dealt with it to be, you know, to be honest, they never emotionally dealt with it. I don't think, uh, they both passed now, but they took that with them. Uh, then, you know, you have to ask questions, what the hell is going on here? One,

Speaker 1 00:52:32 What was it like to site? Just re-encounter those, those events of those feelings, both from a distance and also from writing,

Speaker 2 00:52:40 You know, yeah. Difficult, uh, you know, the worst is fiction. You know, it's funny, the work is fiction, but the emotions are real, you know, and that's the, the bridge, if you like. And I think for it to be real to the reader, it has to be real to the writer, especially if you, you know, you want to, like I say, if you want to write, then I think you have to engage with real things. And they say writes about what, you know, you know, it's kind of the, you know, it's, it's true in that sense. Well, it depends what your rights, you know, I mean these crime mysteries, you know, and it's kind of like, you know, it's show reflection, it's a mystery. And I hope people read it and paid standing and, you know, have no interest in the wider subjects if you'd like they get into it because it's a good story. Fine. Great.

Speaker 1 00:53:38 Yeah. Finish each chapter with a cliff hanger.

Speaker 2 00:53:43 I don't watch coronation street for years.

Speaker 1 00:53:47 Well, you just wanted to do it. It's like a mystery throw. Did you read many of them before? Have you found other genre or was it just one of those things? It's not like everybody knows what mystery is.

Speaker 2 00:53:55 Uh, I've read every denial. It was a big reader from very early age. I read everything that came into the house and started with me. One was Catherine Cookson novels. Uh, and then my brother was a shop steward and a local factory. And I used to read all his union books and everything else he brought back in, but I would read everything I could get why these mysteries, because I, okay. Two reasons. One, because I want to take the reader with me on this journey and through these stories. And, uh, you know, they engage with this. They know what to expect with a mystery and they can feel satisfied going along. And hopefully they will also learn something through the process of, uh, reading this ministry. So it's one to answer the chain, but, you know, while, uh, you know, just bigger drama unfolds around them and to get people thinking that is another reason, and this may sound weird, but I think it's true.

Speaker 2 00:55:00 I don't think many working class races or people are allowed to write literary fiction. Uh, you know, we're accepted if we write romances or through crime or crime, or, you know, other genre fiction. Why? Because, you know, that's what we know we're working class. We're not high flown. And, you know, we can't express emotions in a literary way. None of which is true, but it's partly what the publishing industry expects and does. And so, you know, I said at the beginning and I mean, I was lucky to get published and, you know, I accept that and I'm happy with Dan. I'm not complaining, but I know that, you know, for writers who don't want to write and you John reformer, then they really struggled to get anything published.

Speaker 1 00:55:47 What are your plans for the rest of St Patrick's day?

Speaker 2 00:55:50 Well, uh, I'm going to be back in Liverpool for this. So there is a, uh, apparently a St Patrick's day parade planned. And so I will go, we'll have a look at that with the kids, if it's, uh, if it's going to be safe. And that sounds, that sounds weird to say, but it's actually, you have to be conscious of it because there could be, you know, uh, elements of the orange order or whoever you take exception to it. So obviously I'm not going to go there with the kids if there's any of that. But, uh, but yeah, so I'm going to have a look at that maybe, but maybe, you know, we will definitely do. I think we'll definitely go to the Irish club in Liverpool, uh, to celebrate at some point urine that day. And there's lots of outage Forbes around Liverpool now, so there'll be flags out and that kind of stuff, and yeah, and in fact, you know, what they do now, they tend to live a buildings green. And so, you know, it's kinda, you know, just the things operate on different levels, don't they?

Speaker 1 00:56:58 So this brings me to my final question, um, which, um, is the one that I ask, um, pretty much all of my interviewees, uh, particularly on St. Patrick's day. So what does being a member of the Irish diaspora mean to you?

Speaker 2 00:57:12 Yeah, well, it's, you know, it is who I am. It's where I'm from. Uh, I, where I'm from is no, just the geography. You know, it's taken a long time to realize that where we are from is what we are a product of. My parents were, my dad was born and raised in Ireland and my mom was raised by Irish parents and they made me

Speaker 1 00:57:41 Thank you very much.

Speaker 2 00:57:43 You're welcome. Thank you, Doug. Take it easy, mate.

Speaker 1 00:57:48 You've been listening to the plastic podcasts with me, Doug Devani, and my guest Jack Burns. The tale of Nellie Bly was provided by Nathan Mannion and music by Jeff. Find out more about

[email protected]. Email

[email protected] or follow us on Twitter, Facebook or Instagram. The posted podcasts are supported using public funding by arts council, England.