THEME MUSIC

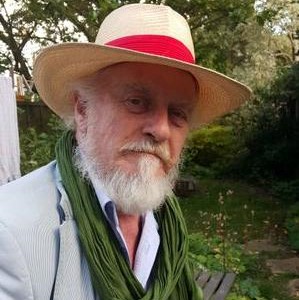

DOUG (VO): How you doing? I’m Doug Devaney and you’re listening to The Plastic Podcasts: Tales of the Irish Diaspora. And today we are honoured- and I don’t use that term lightly - to have as our guest Bernárd Lynch. Born in Ennis, County Clare, Bernárd Lynch is a psychotherapist who was ordained as a Roman Catholic priest in 1971. He remained a member of the clergy until 2012. As Father Lynch he founded the first AIDS Ministry in New York in 1982 before moving to London. In 2006 he became the first Catholic priest in the world to have a civil partnership. in 2017 he received a proclamation from New York City Council honouring his services to the city. In 2019 he received the Presidential Distinguished Service Award from President Michael D. Higgins, and in 2022 he’s the guest on The Plastic Podcasts. It’s a heady rise indeed and so the first question we ought to ask Father Bernárd Lynch – how you doing?

BERNÁRD (Int): I'm doing well. Yeah. I mean, what can I say? I mean, my primary attitude is one of gratitude to - number one, be alive when so many of my contemporaries died in their twenties and thirties. So I mean, I've lived, living? Lived? Living into a ripe older age and that's wonderful. And nothing I take for granted.

DOUG: Yes. You were saying when we were talking about your ministry in build up to this, that COVID was like a tea party by comparison.

BERNÁRD : Yes. I mean, it's like the wars. I mean - I don't think people can comprehend, never mind understand the devastation and the accompanying quote unquote shame, guilt, condemnation, judgement, lack of hospitality, lack of care, lack of any commitment on the part of the establishments, both state and church to these young men -my gay brothers primarily - at that time. I mean, homosexuality then was, well, certainly it wasn't where it is now, thankfully where it is now. People were condemned and blamed for their disease. Whereas in actual fact we never condemn people for getting cancer because they smoke a lot, nor should we. Or indeed getting liver cancer, cause they drink too much. But we, reached a new low in judgment, of these most unfortunate. And - what would I say – ignominious suffering that these people endured. And so they remain for me and became for me, I would say, my Paul on the road to Tarsus conversion where I lost all …inhibition is the word I would use in speaking out and in trying to do what I could to ameliorate and alleviate this state of affairs.

DOUG: You talk about a Saul of Tarsus moment. Was there an actual moment?

BERNÁRD : Well, I mean, you know, I think Nietzsche has said, the first death is the only death. And I mean, there is a truth in that. It was an accumulation of moments because I was doing on average three funerals a week and visiting hospitals up and down the east side and west side of New York city, to try and get some succour to people who were not necessarily Catholic or, indeed, believers, but, you know, a woman or man in that stage of vulnerability and peril, I mean, what they most need in my humble opinion is friendship, a helping hand and some kind of openness to the fact that the helper, namely me, doesn't know what he doing.

There's no manual for this. There's no way that woman or man can enter into the moccasins of someone in that state, other than just stay with them and learn from them. They are the ones who give – they are the teachers. We who are working with them, simply the students and each person is so different. Each person is unique. Each person is looking for hope in hopeless. And I guess even at this – it’s forty plus years later - I still have in my faith a hopeless hope. I have no proof of anything but I hold onto that hope that there is something more. That these boys - men - are in a better place. I think without that I could not have kept going. I could not keep going. As I say, if you want it’s a belief and there no empirical proof for it whatsoever but what is the alternative? Kierkegaard said the alternative is suicide and some of my friends did commit suicide, because the pain mentally as well as physically was too much.

DOUG: These were bleak times. And looking back, even from my own perspective, it's almost impossible to relate them to the times that we live in now. Do you think there's a danger of that being forgotten?

BERNÁRD : Yes. I mean, I would say yes and at one level it's, you know, we move on, life goes on. Life is for the living. Personally don't want to burden with the pain of our history and we all, I mean, nobody has a monopoly in suffering, you know? The world breaks everybody, and if you are strong enough, you survive and thrive at the broken places. And maybe the gift is - The Lakota Sioux Indians say when the gods give us a burden, they also give us a gift. Well for me the gift – one of many – of the AIDS pandemic is the gift of compassion. Compassion is the heart of all morality, as far as I can tell. And, we had nothing to lose at that time, so much was taken away. And, at the same time, I mean, one also in those broken places finds a joy in life, the joy to be alive. The tremendous joy at the gift of life, which is, you know, such a grace, you know? I mean some die at 20, some die at 80. Some don't get to live at all, you know - they're just die at birth. And so there is a renewed appreciation and celebration of human life that is so precarious and can be sniffed out like a candle at any moment.

DOUG: Going back, if I may, through your life, you were born the eldest of six, yes?

BERNÁRD : Yes.

DOUG: And that was in Ennis in County Clare.

BERNÁRD : I was in Ennis, yes. My father worked for the railway CIE and my mum was, as most women were at that time, a mother and housewife.

DOUG: And you felt a calling, to join the priesthood - when we talked earlier, you said that it was as much a sense that you had a need to engage with your spirituality rather than any particular religion.

BERNÁRD : Yeah. I mean, to me, it's a philosophical way: it's an ontological reality. Some people are born to be poets. Some people writers, some people ,plumbers, some people doctors, you know? It was in the gift of the gods to me that I, at a very profound level, felt the need and indeed the calling to do priest, to do shaman, to do witch doctor, to do bardash, to do a druid, in my own culture. But as it so happens because of the coming of Christianity to Ireland it was priesthood that gave me the license to practise and to serve in that way.

DOUG: And what was your parents' reaction, when you announced that you wanted to join the priesthood?

BERNÁRD : I think, they knew. They knew for a long time. Because as a child, I used to dress up in my mum's dress and celebrate mass with water and Marietta biscuits and so they - I was always playing at mass. I was also fascinated of course, by the church, the Pre-Tridentine church. As I've already stated, the operatic theatrical Broadway show of High Mass - Tenebrae, benedictions, vestments, flowers, candles, Gregorian chant. I mean, it was almost, and sometimes better than Broadway ,and of course it was free to all of us, I mean, going to church was - with due respects to everyone - it was a form of entertainment as well as a form of socialization, as well as a channel into something much bigger, much greater than ourselves. Catholicism being a world religion and universally acknowledged for its contribution to arts, to music, literature etc etc.

MUSIC

DOUG (V.O.): You're listening to The Plastic Podcasts. We all come from somewhere else. Find us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Born and raised in Ennis, Bernárd Lynch has become a legend in his own lifetime, whether it’s as the “AIDS Priest” of tabloid headlines or for his objections to the Catholic Church’s views on sexuality. We talk about those objections and the opposition he’s faced later, but first I want to know about the legend’s early lifetime. What was he like as a child?

BERNÁRD (Int): A pain in the ass, maybe to some people. I was a very gentle boy and was denigrated sometimes as a sissy boy, which of course at that time was quite common for boys. I was never effeminate. Not that I have a problem with effeminacy, but I wasn't. I was a very able athlete. I won the cross country championships many times. But, when I say yes, I was the combination. I was a holy kid, because I'd always be looking for, you know, reasons: “let's go to church” or “let's do something”, you know, like say the stations or visit a holy well or go to a shrine. And that definitely was different and did not make me endeared to my comrades who were more into cowboys and Indians and trucks and all that kind of thing.

DOUG: So I was going to ask if you went to the cinema much or anything like that?

BERNÁRD : Yes, I went, as often as I was allowed. I mean, we were poor, so going to the cinema was indeed a big treat. We would be allowed occasionally - as I got older a little more, and I loved it, very, very much living out my fantasies, particularly in musicals. South Pacific, Oklahoma, Carousel, so on, so on. I saw those movies as a child and fell totally in love with them as many young gay boys at that time did, because they became the apotheosis of power. We were powerless. I mean, we didn't know who we were. We didn't fit in. We knew we didn't fit in. We had to be careful in expressing our feelings. You know, I had some very close friends, the difference being they did quote unquote love and respect me, and I have very excellent memories of them.

But the tragedy is I fell in love with them. They loved me. There's a huge difference. And particularly as I went into my adolescence - pubescence, adolescence - I now know I was in love with some of those boys. And then of course, they naturally and necessarily drifted towards the opposite sex gender and fell in love with the most attractive girl to them. Whereas I was still kind of stuck in a very emotional, romantic and painful realization that my feelings could never be expressed. Or if they were, I would be moved to the local mental hospital.

And, you know, all I wanted to do was hold my best friend's hand. And yes, I did imagine, dream my, if can kiss him, but, oh my gosh. You know, my church, the Catholic church condemns sex between same gendered people, but sex was the furthest thing from our minds. We were normal adolescents in an abnormal world, whereas the world and the church would say we were abnormal in a normal world. Well, no, thank you very much. We were given this gift of gayness that was annihilated and practically beaten out of us, especially women and men of my generation. And those of us through gift and grace were strong enough to survive, lived long enough to fall in love and to marry the man we loved.

DOUG: When you mentioned that your parents always knew that, you would join the priesthood or had that spiritual aspect to you, do you think they also knew that you were gay?

BERNÁRD : No, I don't think so. I don't think anybody knew anything about gay in that world. No, the language didn't exist. The comprehension, the ignorance was so profound. And so invincible not only in Irish society, but in an English society, American society. I mean, that's the great achievement of patriarchal heterosexuality - that it can totally obliterate, even sophisticated and educated people's, knowledge by the hegemony of unmitigated power. And it's attempting to do that again as we enter into Roe versus Wade.

So my parents: my father was an educated man and involved in politics. I mean, at the very most, he knew that Bernárd was different, but to have words like “homosexuality”, I even doubt it was in his dictionary. Although when I came out to him, years later in 1982, it was extraordinary his response because he said to me. I said, you know, whatever I said, you know, I'm gay - because the word “gay” had come into vogue at that point.

He said, that's the way God made you.

And I kind of said, wow, that says everything. That says everything. So he knew God made me different, but he couldn't have used the words homosexual or gay. When I did come out to both parents, my mum also - she had only difficulty with the suffering she imagined that I would have to endure. And also she had difficulty with the fact that I took so long to tell them. ‘82, which you know, was a long time ago. It was still criminal in Ireland.

And we didn't have any of the rights that we have now. So they probably had an awareness of my difference, but to convert that into a knowledge, I wouldn't feel free to do that. I'm very aware of the hatred that some people - fundamentalist Christian Catholics, so on and right wing people - have towards us. And they will not be satisfied. I mean, it's happening as we speak. It's not just Roe versus Wade. It's the whole movement of women, who are intrinsically linked with our sexuality because, after all, we were persecuted because we were like women. So if women are not free, we're not free. I mean, to be a man in love with a man and to engage in sexual congress was perceived by ignorant, straight people as to be like a woman.

So misogyny and homophobia are the different sides of the same coin. And there is undoubtedly the next thing that under fire in the US - I’m no prophet, but I don't think you have to be - will be that the marriage of same sex people will be declared unconstitutional, and so on and so forth. And, as you know, that there are different states, - Florida and Texas, and so on - trying to, you know, completely wipe out any education around gay, LGBTQI stuff in the schools and not to be taught to children and transgender rights: you know, off the radar. So, there is a right wing swing, as we know in the world at the moment through the Ukraine war, our government here, government in the states though under Trump. Ireland is a bit of an oasis at the moment in terms of the freedoms and the tremendous moral compass it’s providing to the world. ButI hold my breath, not because I don't believe in the new Ireland, the free Ireland, the beautiful Ireland that I have come to see from the distance and experience in fact, when I'm there. But we in the west, you know, we always - positively or negatively - we're inclined to follow America.

I mean, the feminist movement started in the states. We followed. You know, the civil rights movement. We followed. The gay liberation movement: that we followed. And Ireland being on the outer cusp of the European continent, you know, is slow because of its location and its monolithic population - more or less – it’s changing thankfully , as more immigrants come in and we embrace them. But, it's not that the UK or Ireland would want to, I hope, roll back the tide in human and civil rights. But these people who are trying to do that, these are multi-billion dollar investments because ultimately it's not about sex.

Everything is about sex, except sex. Sex is about power.

And it's the power of the dollar that ultimately will become the tail that wags the dog. And I'm scared of that. That people will yield. People in power will yield to the power, the greater power, the bigger buck, BOOK. Book. And that scares me. That scares me, whether I talk about here in London or whether I talk about Dublin that scares me, that we may be - we may be forced to do things we wouldn't otherwise do because of those who will hold the key to the safe.

DOUG: Such as?

BERNÁRD : Well, to roll back - I mean, Roe versus Wade is not just about abortion rights. It's about women's freedom. And there is , unquestionably to my mind, that there is a huge investment in patriarchal heterosexist society to keep power that way. You know, man on top of woman on top of children. That's how the world has been and major way is, and so they, these people, wanted to revert that, in the strongest and most efficacious way possible. So they will undermine women and their freedoms and they will undermine women and men who are quote unquote sexually different and their freedoms in order to keep the money and the power flowing the way they think it should. And in the hands of those who are the 2%, if that is correct, who control the purse strings.

MUSIC

DOUG (V.O): We’ll be back with Father Bernárd Lynch in a moment. But first it’s time for The Plastic Pedestal: that part of the podcast where I ask one of my interviewees to talk about a member of the Diaspora of personal, cultural or political significance to them. This week, Brian O’Neill of Dimple Discs talks about his friend Sean O’Hagan

BRIAN (Int): I mean, I've known Sean for many, many years and we’re very, very different personalities. But I still learn from Sean and I would hope vice versa. We've got a friendship that's very alive and I've got a huge amount of respect for him as an artist as well. Very well respected in Brazil. I don’t if you know the Tropicália Music movement from Brazil. It was the post-Sergeant Peppers, but politicized, things that the military regime crushed and they brought it to the Barbican and the Brazilian guy said, we want Sean to do the arrangement as he’s friendly with loads of them. Oh, it's like, wow. Immensely talented. Still learning, still got astounding - I mean, he has actually got much more connections to some things than I do, but he wouldn't think to mention them. I'm quite actually practiced in having to express myself because of the housing job. I would just have to express myself and make connections with people very, very quickly in public meetings. So I kind of, trained myself in that, but Sean's - yeah, he's some talent. Yeah. He's, Anglo Irish more than - he probably considers himself - who considers themselves, whatever, you know? It's all identity, isn't it?

DOUG (V.O): Brian O’Neill there, and if you want to hear more of what Brian has to say, why not listen to his interview? Simply go to our Episodes page at www.plasticpodcasts,com, click on his name and listen at your leisure. Also available on Spotify, Amazon and Apple Podcasts.

But while you’re at the website, why not subscribe? Just go to our go to the Home page at www.plasticpodcasts.com, scroll on down to the bottom, enter your details in the space provided and one confirmatory click later the plastic loot of the world shall be yours. Details of our latest podcasts, personal blogs and all kinds of info. Just for you.

Now back to Bernárd Lynch. In 1987, Father Lynch found that he was to face charges of sexual abuse of a 14 year old student. The case was thrown out court. Father Lynch was not simply found not guilty he was completely exonerated of all charges. Despite this, the case tore his life apart and still pains him to this day, but he has been good enough to talk about it with us here. Firstly though he discusses his views on sexuality and the church.

BERNÁRD (Int): To me, sexuality is about relationality and many priests - some would say the majority of Catholic priests - are in fact relationally orientated gay. And as you know, in the Catholic church, gay is anathema. They still teach that to be gay is to be disordered in your nature. And if you express it sexually in a loving relationship, that is evil. Now I have opposed that from the beginning. because basically I think it's the teaching that’s evil, not the act of love making. And you know, that became the, a facciori reason for the charges: that I was challenging the church in their own language, on their own terms.

And, as you know, they found this boy to make these charges against me, and he was promised 15 million dollars if he would testify against me. And he never thought, of course, that I would go to court. Because my attorneys, they told me, I hadn't a hope in hell if I went to court. That I was up against the two most formidable institutions in the world, the Catholic church and the FBI. And in fact, one of my attorneys briefed me and said, “Bernárd , if you’ve got any sense we will find you a new identity, we will get you a new passport because you’re not going to win this case. It's nothing to do with you.” I mean, they were very clear. This has nothing to do with you. The case was so flimsy, there was only one allegation by one boy, even though they lied at the beginning – they said there were many. An allegation by one boy, and all your years as a priest, in the school and in therapy, one allegation by one boy. So it's not about you. This is about, and of course it is true - this is true: they were wise men - and they were men - I was being held up there as an example to any woman or man who stood against, particularly the Catholic church and its institutions: that this is what happens to you, Jeff, if you take that stand. So don't you dare.

And the interesting thing about it is there never has been since then. And that was 1988, I went to trial. 89 I was exonerated. There never has been a priest since, who’s challenged that teaching publicly. So they won if you want. You know. They won. I don’t know if you want to say want to say they won the war or they won the battle. I don't think they'll ever win the war. I think and I hope that always will be women and men like Mary McAleese, the former President of Ireland, who constantly says what I'm saying: that this teaching is evil and destructive. So they won that. And that was the reason for it.

And, as I say, by the luck of the draw, I did go and face my accusers. I returned to the States, voluntarily. My trial defence at that time cost $100,000. Now I didn't have a penny but my order, the Society of African Missions to which I belonged up until my ripe young age of 65 - they are the ones who paid for it. They paid for my defence because, in their goodness, they believed I was innocent. They knew it was a setup by the church. They knew that I was being scapegoated. And so when I was interviewed by them initially, and they said to me, “Bernárd , this is atrocious. Like, you know, we know you've been involved in AIDS ministry. We know you have been advocating before City Hall for LGBTQI rights, did you do this? Did you molest this boy?” I said, absolutely not. And they said, “We believe you.”

Now they had no evidence. All they had was my word. Said we believe you. We believe you have been a patsy, set up, a scapegoat and we will pay for your defence. Thankfully they made the right decision. And thankfully my exoneration was their exoneration. So that's how my trial was paid for. I couldn't possibly have mounted $100 000 in a hundred thousand years, you know?

DOUG: You talked a lot earlier about compassion. Was it difficult to feel compassionate towards the Catholic church under those circumstances? Was your own personal compassion tried there?

BERNÁRD : Well, I mean, institutionally, I don't have any compassion for the Catholic church's institutions, none whatsoever. Particularly in relationship to women and LGBTQI people. I mean, I always make a distinction between the institution and the actual people. There are, as there are in all institutions - whether it's marriage or the church - there are some very good people, who live their life that they are intended to live to the very best of their ability. And so when I talk about the Catholic church and when I speak min condemnation of my church, it is the institutions that perpetuate the lie around women and around us as LGBTQI people.

So even within the church - I mean, the church, as you know, is 1 billion, 200 million people. The largest known religious denomination in Christendom. Within that you had my order saying - you know, it was like a civil war if you want - saying, we are not going to go with the institution's charges against you, we are going to fight them. And you know, that takes a little more, I suppose, understanding that the church is not a monolith. Never was, never will be. And the difference between an Irish Catholic and an Italian Catholic is not just countries apart, it's a whole culture, a whole history, a whole knowing that is so different. French Catholic and Italian Catholic, and Brazilian, English Catholic - very, very different, but held within this certain umbrella called Roman Catholicism. But, as I say, the difference between an Italian Catholic and an Irish Catholic is that Irish Catholics enjoy confessing their sins more than they do committing them.

DOUG: What are New York Catholics like then?

BERNÁRD : Well, they would be an amalgam of, you know, all the ethnic minorities. The Italians, the Germans, the Hispanic, the Irish, Italian and so on and so on. So there was a mixture, except that in New York, particularly, and in the large diocese - New York, Boston, Chicago, so on - the power dialectic was primarily in the hands of the Irish. Of course for the Irish immigrant, even here in the UK and in the States, the Catholic church became a defence against the WASP, anti-Catholic anti Irishness. So they became - the church became for us - a place of succour, a place of refuge, a place of hope when we were discriminated against because we were Irish and Catholic and the church in that sense, and I hope nobody would deny this - I mean, they gave us the greatest education, even in my home country. The most educated population in Europe is largely due to the gift of the Catholic church, against the awful visitation of colonialism.

And we are grateful to the church for that, but we are not grateful to the church for, you know, becoming in many ways worse than our colonizers when they got the power. You know, power corrupts, divine power corrupts, divinely. And they really did a job in the way they have abused women and children as you well know. So again, you know, nothing is black or white, it's all shades of grey. They gave us the gift of freedom at a level to be educated, but then they took it back by abusing us in ways that are absolutely horrendous.

MUSIC

DOUG (V.O.): You’re listening to the Plastic Podcasts, Tales of the Irish Diaspora. In 2007, Father Lynch and his life partner Billy Desmond, became legally married. The first ever Catholic priest and partner to have a civil partnership. It’s a love that began with Bernárd ’s decision to move to London in 1992.

BERNÁRD (Int): I came to London because I was then, you know, I was known as the AIDS Priest in media. Strange title. Because I was the most out priest doing AIDS ministry. And, as you know, Channel 4 have done, did a first documentary “AIDS: A Priest’s Testament here”. And that of course grabbed world attention in the English speaking world. So I had lots of invitations to come here and talk to secular organizations as well as church organizations about my work and what it meant to be working with people with AIDS and how to do it.

Yeah, I smile because “how to do it”.

So I used to come over here quite a bit and then after my trial and - again, Channel 4 came and did a documentary on that and then a subsequent documentary on the aftermath of that. So I was becoming a cause célèbre in New York and I couldn't get away from media and that kind of notoriety. And I was exhausted, absolutely exhausted, not only from the AIDS work, but from the attack on my very soul, by my church and the FBI.

So with the help of my therapist in New York, I decided a change would be as good as rest. So I secured a job here as I told you with London Lighthouse, Carra - the care and pastoral resource centre in London - for three years. So I came over 92 and worked and found London very welcoming. Although a huge difference in what it meant to be Irish here. I felt the racism of the English state, which is still there at some level towards Irish people. After all it’s while I've been here in the nineties that we’re declared a separate ethnic group because anti Irish racism is endemic and systemic - still there. I still come across it, unfortunately. I never knew that in the States. And it was shocking ignorance - really shocking. And hurtful, given the great contribution our people have made to this country. But I settled here and I like it here. And then of course I found the love of my life here.

Billy had seen me on telly, which is not a good place to see anybody. I mean, when you become a legend in your own lifetime, that's very dangerous, especially if you believe it. Billy had seen me on telly and we were at a party, for a friend of his, and that was ‘93. And he came in and, you know, he took a shine to me and I could see he was a very attractive young man and Irish - which didn't mean A or B to me. I mean, I had all kinds of people of different nationalities and ethnicities and colour and creeds as my friend, which I would in my ministry anyway, because as I said, my ministry was never sectarian or exclusivist.

He asked me, would I go for a drink after the party? And I said, sure, why not? And I knew he was coming onto me. And I was kind of being very - and he was 22 years younger than me - and I was kind of flattered, but I kind of said, when I knew he was coming, I said, Billy, look, you're gorgeous. You're beautiful. I'm totally flattered, you know? I'm sorry, I don't want to go home with you. I said, you know, I presume you want to go home with me, but I don't want to do that. I have a feeling that you want more than just a roll in the hay, and I'm not up for anything at the moment. I’m just here and in no fit shape for a relationship. I'm in therapy here and I'm trying to put my body and soul back together. And was, you know, he said, can we be friends? And I said, sure, we can be friends. If that's what you want and enjoy our friendship.

But of course, Billy from the word go was interested in more than a friendship. And I made it hard for him, kept batting him off. And I mean, that was three, like - I would say five? - yeah, five years later - we were still friends and Billy was still kind of, you know? I knew. I thought he was wasting his time.

So one Sunday afternoon, you know, he was in my flat, I said that to him. I said, Billy, you’re wasting your time. Like, why don't you go and find - there are lots of fish in the sea apart from me and men in a lot better shape than I am, and much more capable of loving you than I am. You're a beautiful man. And I will always be friends, but I want to break the friendship now because you are still pursuing a romantic relationship and I know it.

So he left my flat in tears and I did what I've always done when I'm under pressure all my life from the age of 11. I'd go running. I love running. It's my passion. It's my prayer. I love running. I still run a bit, even though I'm a bit of a crock these days, but I still love running. And I went for my run in Regents Park here and I was coming back from my run and coming down Parkway. And I saw this figure at the bottom of Parkway as I was coming down and it was Billy. Literally in, you know, in another world. Out of it. Just walking along with his head down. So I had a choice of turning back and avoiding him or facing him so I came towards him. And then I bumped into him. I could see his eyes full of tears and it broke my heart. It broke my heart. How could I hurt love?

How could I hurt love like that?

And that was it. I just said “Billy, I'm really sorry. I'll try.” And that was it. That was our engagement .

So we had a blessing in 1998 because we couldn't get married or civil partnership or anything. We had a blessing . A Cistercian monk came from Snowmass Colorado and blessed our relationship in the company of our friends and families. And then of course we went on to have a civil partnership and had a marriage in County Clare in 2017. My wildest dreams that I would ever marry the boy, man, I love. So we're still together. It works. it works

DOUG: Love will win.

BERNÁRD Love, win. As I love to say, time is on the side of love. Only those who love know the true meaning of time.

OUTRO MUSIC

DOUG (V.O): You’ve been listening to The Plastic Podcasts with me, Doug Devaney and my guest, Father Bernárd Lynch. The Plastic Pedestal was provided by Brian O’Neill and music by Jack Devaney. Find us at www.plasticpodcasts.com. Email us at

[email protected] or follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. The Plastic Podcasts are supported using public funding by Arts Council England.